Chairman of the Board: Kelly Slater

Los Angeles Times

There’s nothing conventional about the group milling around in the San Diego Convention Center. A CEO in striped shorts is negotiating with a buyer who has a pierced tongue and tattoos on his bald head. A retailer with a parrot on his shoulder haggles with an apparel-company rep, who is topless under her clear plastic raincoat.

Outside, teen-age girls wearing halter tops and boys balancing on skateboards beg passersby for passes into the hall, as if this were a rock concert, not the trade show it is. Suddenly, one girl squeals and points in the direction of a young man not much older than she is. As she and her friends stampede in his direction, the man flinches, then smiles nervously, dutifully signing photos and posters and posing for snapshots. He makes his way into the building and winds through the crowded aisles until he arrives at a Tahitian-style hut. There, a dozen buyers, sellers, executives, PR agents, reporters, photographers and fans are waiting for him. Again he hesitates, then smiles and deferentially shakes hands all around, signing more autographs and answering questions.

This is the Action Sports Retailers Trade Expo, and world-champion surfer Kelly Slater reigns supreme. After a few disastrous years, board sports are again on the cutting edge of youth culture. Snowboarding is one of the fastest growing sports in the country and surfing is everywhere–in ads for trucks and soft drinks, fashion spreads in Rolling Stone and MTV videos. To a greater extent than in the past, mainstream advertisers, including record, car and telephone companies, are buying commercial spots on surfing broadcasts. And the sport may even get some respectability–the International Olympic Committee has tentatively approved surfing for a future Summer Games. “All eyes are on these kids,” says Bob McKnight, co-founder and chairman of Quiksilver, the world’s largest surf-wear company. “Surfing is hard, groovy environmentally, and there’s Kelly Slater.”

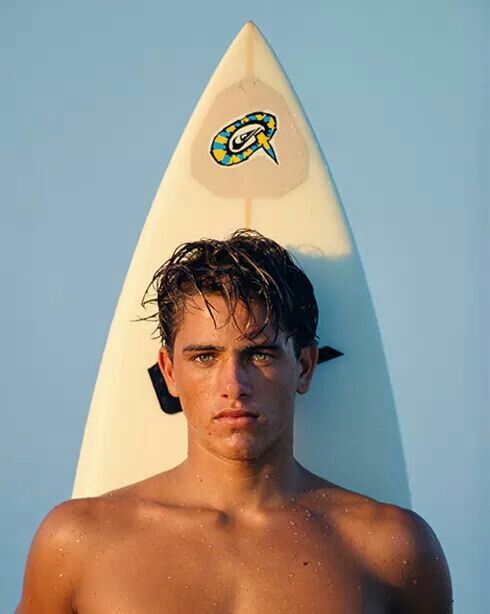

Slater is just under six feet tall and compact, with a low center of gravity that helps ground him on his surfboard despite his height. Most surfers tend to be on the small side. There are rails of muscles along his chest and back. The Florida surfer was on People magazine’s list of the 50 most beautiful people in the world in 1991. And as his sponsor, Quiksilver knows the only thing that Slater does better than master the sport is market it. “Kelly sells clothes like no one in this sport ever has,” McKnight says.

Surfing drives a $1.2-billion industry, nearly half of it fashion: baggy trunks, hooded flannel shirts, jeans and skater shoes, all mostly bought by surfer wanna-bes, many of them living thousands of miles from either coast. Which explains why the industry views Slater as heroic. He is its first marketable champion, whereas in the past, many have been too eccentric and media wary. Mickey Dora, one of the more well-known surfers of the ’60s, reacted so adversely to the overexposure of the sport that he quit the circuit after a hostile farewell: He mooned the judges at the 1967 Malibu International Surfing Contest. Many of the big-name surfing champions of the recent past, such as Nat Young and Tom Carroll and four-time winner Mark Richards, are Australians, though Americans now dominate the pro ranks. The last American champ, Tom Curren, lived for many years in the South of France. Though he’s back, Curren is media shy and rarely returns phone calls.

Slater, on the other hand, has been amiable and eager to please ever since he began winning an unprecedented string of amateur contests when he was 8. He turned pro at 19, winning the Association of Surfing Professionals World Championship Tour (WCT) in 1992 and 1994. His surfing was lithesome and combative, and his good looks didn’t hurt. Not surprisingly, the combination has led to a career, which includes television and recording deals, like no surfer has ever had. “He’s the first major crossover star the industry has seen,” McKnight says.

“He’s the perfect champion,” adds Michael Kingsbury, a spokesman for the Surf Industry Manufacturers Assn., which represents the companies that make the boards and clothing. “No one has ever been in the position to do more for surfing.”

And at the convention, Slater is the All-American champion–congenial, modest and cooperative. But he is also reticent, embarrassed and uneasy. Despite his looks, he is not a hunk; he is shy and awkward, sometimes even morose. “Just when I’m in the water I feel at home,” he says.

As his friend Brock Little, one of the world’s greatest big-wave surfers, later observes: “He wants people to like and respect him so much that he never says no, but his fame and success don’t seem to feel very good to him.”

Indeed, while he smiles and signs, smiles and poses, Slater looks somewhat bewildered, as if it’s all gotten a little out of hand. “Surfers think you’ve got no soul if you make money, though every one of them would love some,” he says later. “In some ways, this all seems like a contradiction to the purity of surfing. It changes the way I feel about the sport. It used to be that surfing freed me from everything, but not anymore. Now I sometimes don’t even feel motivated to surf. Sometimes it feels like a job, and that’s what you don’t want to happen.”

*

A hundred or so yards beyond a gravel-and-shell beach on the North Shore of Hawaii, enormous and spectacular waves break, echoing through the cove with a low, ominous rumble. Slater’s entire body responds. His breast swells, his neck broadens, his fingers twitch and his eyes burn. Without a word, he plunges into the water atop his board and paddles powerfully, slipping under a series of sledgehammer waves with sleek duck dives, until he reaches the churned-up ocean beyond the break.

He sits up on his board to rest, then lies stomach-down and begins a measured stroke toward the beach. A sheer, watery cliff catches his big-wave “gun,” a lengthy, book-thin board shaped like a swordfish. He leaps up, crouching, forcing the board’s edge into the wall, a cuneiform trail spraying behind him. As the lip of the wave cascades down, he does a quick turn upward that increases his speed and blasts him clear into the air. He lands backward and slides along the wave’s crest. For a finale, he turns toward shore again and cuts down and into the face, just ahead of the spilling waterfall. He emerges with a wild grin.

When the waves are good, Slater is breathtaking to watch. He surfs with elaborate determination, continually reinventing not only his own style but the sport itself; novices on beaches everywhere aspire to emulate his signature moves–tail slides, 360s, aerials. Some old-school surfers look down on them as sloppy and showy–“slippy slidey” is the derisive description they use–but Slater has developed them with never-before-seen grace. At the same time, he surfs the traditional styles with as much sheer power and speed as anyone ever has.

“He’s redefined the sport,” says Mark Richards, arguably the best competitive surfer until now. “It’s impossible not to be impressed by what he does on a wave.” “He s—s on the old guys,” says Little. “He can ride anything.” Recently, for a friend’s video, he proved it–surfing on a door.

“Kelly is far and away the best of his era,” says Steve Hawk, editor of Surfer magazine. “He’s faster, with incredible style and grace, even in the most perilous situations. You never know what he’s going to do.”

But no matter how rare and remarkable it is to be the world’s greatest anything, virtuosity seems valued these days mostly as a quick route to a Screen Actor’s Guild card. At 21, two years after turning pro, he was offered a recurring role on “Baywatch,” the ubiquitous television show that is seen each week by nearly one-fifth of the world’s population. (In a typical episode, Slater’s character, Jimmy Slade, facing off in a surfing duel with grungy punks wreaking havoc on fictional Tequila Bay, becomes entangled in a web of barbed wire that’s buried underwater. The lifeguards hurl off their T-shirts and, maximum flesh exposed, jump in for the weekly rescue.)

The offers that have arrived since have been lucrative and diverse. Sony’s Epic label signed him to a record deal and Philips Interactive to a starring role in a CD-ROM video game. Other TV shows are in the works, including a hosting spot on a new real-life action program called “Lifeguard” and a show for MTV or another network entitled “Channel Surfing With Kelly Slater.” He has also turned down an appearance on “American Gladiators” (“too dangerous,” his manager says) and a commercial for a deodorant for teen-age girls (“too tacky”).

“Baywatch” has brought Slater considerable fame as a surfer, but it also has caused relentless harassment by devotees of the sport. Surfing is difficult, inaccessible to Americans not living on either coast, and it’s dependent on unpredictable and uncontrollable forces. Plus surfers make a show of being extravagantly anti-Establishment. Like alternative rock musicians, surfers aspire to success but vilify the successful.

The worst sin is complicity in anything that is seen to trivialize or demean the sport, which is notorious for its strict etiquette. Of a surfer’s possible transgressions, worse than trespassing on other surfers’ turf, worse than ditching a board in the path of another surfer, worse even than stealing a wave is, apparently, portraying a surfer on a popular television show.

If Charles Barkley showed up at a neighborhood basketball court anywhere in America and asked whether he could shoot some hoops, the locals would be ecstatic. Yet when Slater recently paddled out in the water off a hidden beach on Oahu’s North Shore, there was no warm welcome. One told him to get out or be killed and then chased him–paddling ferociously, trying to spear him with the sharp point of his board. The world champion reached the beach and ran.

“It’s humbling,” he says, attempting to minimize the scorn, but he cannot conceal how much it bothers him. And while many surfers have forgiven him “Baywatch,” the opinion of Northern California surfer Tim Roth isn’t uncommon. “Sorry, but that’s too much of a sellout to forgive,” he says. “Slater went for the bucks. F— him. He had better not show up on one of my waves.”

Though it’s safe to assume that there aren’t many surfers who wouldn’t go for the bucks, Slater may be the first to transform his talent into a cottage industry. In this, he has been aided by his manager, Bryan Taylor, who saw Slater’s picture in a surfing magazine in 1986 and wrote the “fresh-faced” boy a letter and heard back from his mother.

He took Slater out for what he describes as a power dinner at a Sizzler restaurant. Taylor talked endorsement deals and acting opportunities while the 14-year-old remained silent. Finally, near the end of the meal, Slater asked: “Are you going to eat your cheese toast?”

Taylor negotiated Slater more than $100,000 in endorsements, an astronomical amount for an amateur. Taylor also made deals for posters and calendars and landed the “Baywatch” role. Slater was unsure about some of the ventures–“It happened fast; it’s hard to say no to chances you never thought you’d have”–but he did as he was advised.

His growing visibility increased his worth, and he signed a series of record-setting deals that culminated in a new, five-year contract with Quiksilver. The amount is a secret, but one industry source says that it exceeds $3.5 million. This is beyond his winnings on the tour ($100,000 or so last year) and other ventures, including K-Grip, a surf-products company. K-Grip is important, Taylor says, because “I want to make sure Kelly has an income when he can no longer surf.”

This is a legitimate concern, considering that die-hard surfers often chase waves around the world and earn nothing and then are over the hill by 30. Nonetheless, the money seems to tarnish the purity of surfing, even for Slater. When the money comes in, “you get paid a big number–and you want to keep getting more and more, like there’s some huge number that will satisfy you. It makes you wonder what it’s really about. It seems like a distraction.”

This and other stresses in his high-profile life–the TV shows, the endorsements, royalties, photo sessions, accountants, fan mail, investments, the press–are behind a melancholy that creeps into Slater’s more jubilant moods. He is only 23, and a young 23. He wants to drink, goof off, date, play music and surf not for points but for thrills.

“Half the time I have some obligation,” he says, “but I just want to be with my friends or play guitar and have some fun.” His manager is orchestrating a career “with legs,” but it worries Slater. “If you lose your soul, what’s the point?” he asks.

*

Inside Cyber F/X, a studio on a tranquil avenue in Montrose, Slater waits in a cluttered back room, where he is pursuing one of his oddest career opportunities yet. When the technicians are ready for him, he removes his shirt and sits as still as possible on a chair positioned on a platform. A boxy laser camera slowly orbits him, scanning the surface of his face, head and torso. A three-dimensional image is produced on a computer screen: a metallic bust, twirling on its axis, with Slater’s features.

When completed, the image will be sent to another studio, where a computer-generated body and surfboard will be attached, and then to Silicon Graphics Inc., the Mountain View computer company that commissioned the portrait, to be animated. The moving image will then be placed at the gateway to SGI’s site on the World Wide Web (http://www.sgi.com). Slater’s virtual twin will soon surf the Internet.

Meanwhile, the flesh-and-blood version has other business to attend to. Last year, Epic Records vice president Roger Klein heard him singing some self-penned songs at Slater’s friend’s house in Hawaii, and now an album is in the works.

Slater is debuting his music at the Kona Grill in Solana Beach, north of San Diego, with a thrown-together band called Fear of Hair. The name has something to do with his recent haircut. After years with a wavy, tousled, boyish cut, he has a short buzz. And Slater isn’t the only one in this band making a hair statement. Surfer Peter King has shaved his head, and Rob Machado, No. 5 in last year’s WCT, has whipped his blond curls into a puffy souffle.

When the music begins, it becomes apparent that there is a place other than the water where Slater loses his shyness. He has a voice that is alternately wistful and ebullient, reminiscent of Phil Collins. He strums a banged-up guitar and croons plaintive elegies–one about a woman going to have an abortion and another based on a dream about a former girlfriend. Klein is delighted with the performance. So is the packed audience, which includes loads of adoring young women, who are generally within panting distance wherever the champion appears.

Slater may write sensitively about romance in his songs, but he often describes women as “tasty” and a “perk” of his job. He says he longs for a meaningful relationship, but he is skittish, partly because he hasn’t recovered from the breakup with the woman about whom he is still dreaming and writing songs.

They met in Orlando at a surfing-products convention in 1992. She was 17, a ravishing brunette-maned bikini model named Bree Pontorno. He was 19, soon to become the youngest world champion in history. She accompanied him on the circuit, and for a year or so the couple were pictured in magazines looking blissful and domestic. But the relationship disintegrated and Slater was devastated.

Now he broods when he speaks about his attempts to date seriously. “I confuse girls,” he says. “The second I meet a girl I’m figuring out why it won’t work. I don’t know exactly how you can have a relationship that can work.”

His parents’ didn’t; they divorced when he was 11. In fact, several years ago, in Sports Illustrated, his father’s alcoholism was mentioned in a brief profile of Slater, and the author concluded that “Kelly surfed to ride out an unhappy home life.” Slater was saddened by the article, which he says was unfair to his father, Steve. “It wasn’t an unhappy home life,” he insists. “I have good memories.”

Memories such as the smell of his mother’s suntan lotion; the food cooking on the grill at the Islander Hut in Florida’s Cocoa Beach, where she used to work, and root-beery surfboard wax. His dad’s bait-and-tackle shop, where he and his brothers got worms and minnows for shore casting or trawling in friends’ boats. Slater has surfed almost every day since he was 5. In the evenings, he scraped wax off his board and reapplied a fresh layer. In the morning, he was in the water again, mesmerized, his mother says, by the waves.

Did his parents ever worry that he would turn out to be a surf bum? “What is wrong with being a surf bum?” Slater asks, incredulous that “surf bum” is mentioned in a pejorative way. “I think surf bum-ism is a pretty good life.”

He is clearly miffed. “Look at these guys who have 9-to-5 jobs, sitting behind a computer the whole time it’s light out. They’re not struggling financially, but they don’t have much of a life beyond their jobs. I know surfers who make no money–they probably owe everyone in the world money–but they enjoy every day.”

No, his parents never worried about his becoming a surf bum, and no, he did not have an unhappy childhood.

Alcoholism did color his early life, however. His mother, Judy Rivers (she is remarried to Walker Rivers, a marine mechanic), says: “Steve and I fought about his drinking. It was a mistake to stay with him as long as I did. Kelly was affected more than the other children. He got scared. It made him a little unsure of things.”

Slater remembers following his mother around the house–to the kitchen, to take out the garbage, to make the beds–clutching her leg. He speaks of that time reluctantly. “I was always scared that she would leave. I wouldn’t have blamed her. I tried to be so good so she wouldn’t.”

The unintended revelation jars him and he falls silent. Then he breathes and continues, “Dad finally left when I was 11. You don’t really know what’s going on. You think your life is falling apart. It’s the first real dose of adulthood and of problems to come.”

He devoted himself to surfing, “studying it as if he was studying for a degree,” his mother says from her home in Cocoa Beach. He won his first contest at 8, and he placed third in the U.S. amateur championship when he was 14. Unlike many surf bums, he stayed in school (“What’s so hard about school?”) and earned a 3.85 grade-point average, doing homework en route to competitions up and down the Eastern Seaboard.

After graduating, he turned pro. By 22, he was the youngest two-time winner of the world championship and he had bought a house in Cocoa Beach a few blocks from his mother and a condo in Australia. He spent most of the year surfing the WCT, often crashing at friends’ apartments in Los Angeles when he was filming “Baywatch” or meeting Hollywood executives. The telephone was his lifeline; his mother received calls regularly from all over the world. “We’d talk for hours sometimes,” she says. “He needed to be reassured that everything was all right, that we were here waiting for him.”

*

Slater finally heads home again after several weeks in Southern California (being digitized, meeting and greeting at the convention, filming the pilot for “Lifeguard,” performing at the Kona Grill). His mother is planning a surprise birthday party for him; she explains that “he needs a healthy dose of family and friends.” In recent phone calls, she says, “He’s sounding a little sad.” Bryan Taylor has noticed it, too. “You get the sense sometimes that he wants to run away–not that he would but he wants to.”

The birthday party lasts almost all night. There is guitar playing, joking, dancing. Friends he hasn’t seen for years are there. During the following weeks, Slater gets in some surfing with his brothers–Sean, 26, makes surfboards and Stephen, 17, teaches at a summer surfing camp–and it begins to sink in that he can do whatever he wants; he is on no one else’s schedule. One afternoon, he mows the lawn in front of the single-story, four-bedroom house. He’s moving soon to a townhouse he is buying, and his mother and stepfather will move in here. The townhouse is a half-mile away. The beach where he learned to surf on $5 foam boards is across the street.

But Slater remains edgy and pensive. He can’t shake the feeling that he may not be going in the right direction.

“Sometimes I just want to surf,” he says. “Just for fun. Get out of here and do nothing but surf, surf, surf, get burned by the sun, pass out exhausted at night, and wake up and surf some more.”

To soothe this unease, Slater has moved to a new level of surfing–the big waves. “When you get to a certain point, you’re looking for something different so you get that exhilaration,” he explains. “For me now it’s trying to find the biggest waves I can.”

When the waves reach 20 or more feet, the rush is barely describable. “It is as if you were driving a race car around hairpin turns at 200 miles an hour. It’s that intense. That concentrated. You cannot be distracted for a second. It scares the s— out of you.”

This is what is drawing him to a treacherous Northern California break that last year became infamous when renowned surfer Mark Foo died there. Maverick’s Beach, 25 miles south of San Francisco, is never an easy beach to surf because of underwater caves and rocks. Its below-surface shelf can send waves higher than 20 feet with frightening power.

The waves up and down the storm-battered California coast were as formidable as they get when a number of the world’s best big-wave surfers descended on Maverick’s Beach last winter. On Dec. 23, Foo flew in from Honolulu. A crowd, including photographers in the water, on the cliffs and overhead in a helicopter, watched the svelte, charismatic and fearless surfer wipe out on his first wave of the day, a relatively easy 12-footer.

The next wave, a hairier one, possibly distracted onlookers from watching for Foo. That second wave threw off two surfers, including Brock Little. His leash, the springy cord that attaches a surfer to his board, became stuck on an underwater rock, holding Little below the surface for at least two or three waves. Gasping for air, he made it to the surface when his leash snapped.

Meanwhile, Foo’s friends thought he had gone ashore for another board. But then one of them discovered the front third of his board and then the purple-and-yellow tail piece and, finally, his body.

A week after Foo’s death, services were held simultaneously at Hawaii’s Waimea Bay and Maverick’s. Slater was among the 200 surfers who paddled out in Hawaii. As is the tradition when a surfer dies, Foo’s family scattered his ashes inside a circle of surfers. “Mark was where he wanted to be. He was home,” Slater says.

Now, the champion says he plans to head to Maverick’s the next time the big waves hit.

It may seem foolhardy, considering all that Slater has to lose, but Foo, for one, would have understood. Years before the fatal accident, Foo almost broke his neck when he was surfing at an atoll northwest of Kauai. Afterward, he said, “I realized once again how, for those time-warped seconds, life is pure. There is no confusion, anxiety, hot or cold, and no pain; only joy.”

Of course, in between chasing the big waves, Slater will attempt to win his third world championship on this year’s pro circuit, which runs through December with contests from Japan to Australia to France. The circuit hits Huntington Beach for the U.S. Open of Surfing, Aug. 1 to 6. Former champion Mark Richards, viewed as a kind of guru in the sport, says, “If Kelly wants it, he’ll take the championship again; he’s got the ability.” Adds Little: “If he stays motivated and focused, he’s unbeatable.”

Will he stay motivated and focused? His success and the incumbent distractions are making it difficult, but Slater is taking a first step. He has decided not to do any more episodes of “Baywatch.” “You can’t pasteurize surfing, filter it or change it around,” he says. “I would do a TV role but they’re not going to get me on a surfboard as an actor.”

It is not an easy stand for him–he doesn’t want to hurt anyone associated with the show. But he is learning to listen on land to the same instincts that he relies on in the water, and to defend them with the same ferocity. And Foo’s death seems to have reminded him that the stakes are higher than whether he wins another title.

“I was surfing off the coast of east Java and tried for this wave,” he recalls. “It was huge and dense, maybe 15 feet. It was too steep to ride and I got slapped down into a free fall. My board caught on the face and catapulted me onto the reef.

“I was barely conscious, but my eyes were open and I was rolling over and over in the water; I saw light and then dark, the surface and then the reef. After a while, I thought, I gotta wake up now. I sensed that it was time to come up in the way that a dog senses an earthquake before it happens.”

He looks ahead with solemnity. “Animals are not distracted like I am; they’re not stressing about problems in their life. Their intuition is right there when they need it. I have to figure out how to stay close to mine.”