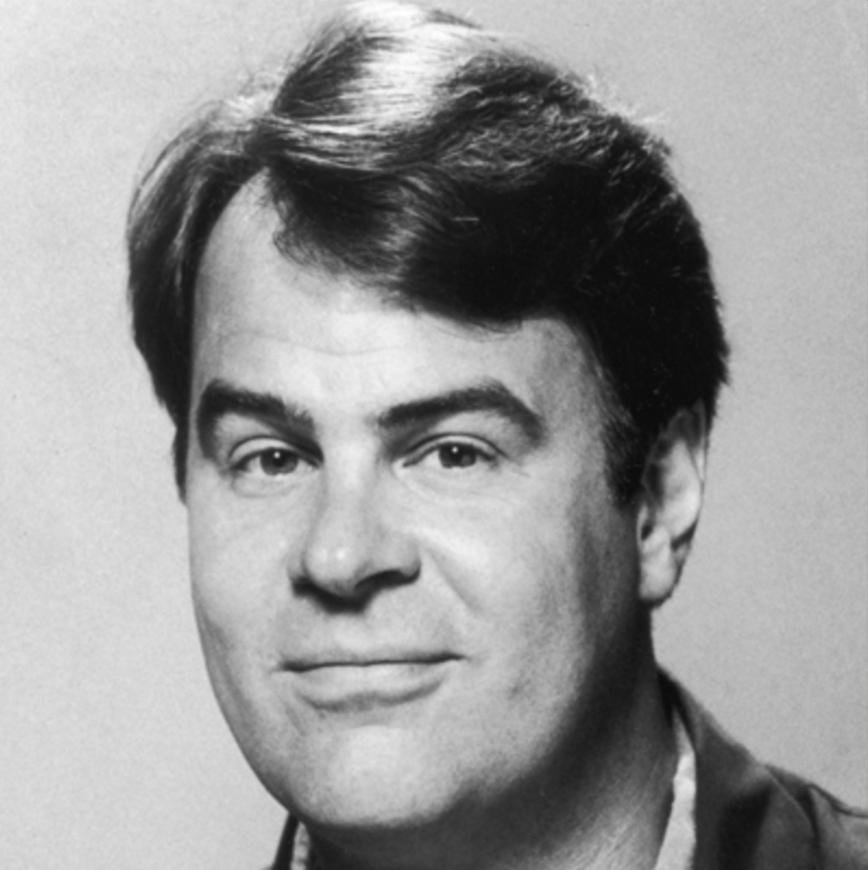

Dan Aykroyd

It's been a grueling 14-hour day on the set of "The Coneheads."

Suddenly, a strange sucking sound echoes off the avails. For the cast and

crew it's the signal that they can go home - Dan Aykroyd is ripping the

plastic cone off his head.

No longer dressed like Beldar the head Conehead, Aykroyd is

shorter and happier. But he still has work to do. He's one of the

writers as well as the star of "The Coneheads," which he helped create as

a skit back in the golden age of "Saturday Night Live." Tonight,

representatives from a toy company need to meet with him about a line of

Conehead toys, the assistant director needs to discuss tomorrow's shots,

his secretary hovers nearby to talk about juggling his schedule. When he

finally gets to pass through the guarded gate to the parking lot, he's

spotted by a few lingering stage-door johnnies. One, an eight-year-old

boy, grabs a friend by the shoulder and squeals, "Look at that. It's Bill

Murray!"

Aykroyd smiles and shakes his head. "Close," he says, "but no."

"I know you're a Ghostbuster," the boy counters. 'Aren't you?"

"That I am," replies Aykroyd.

Indeed he is. Dan Aykroyd has been a Blues Brother, a Ghostbuster

and a Conehead. He does killer impressions of Richard Nixon and Jimmy

Carter. He's won an Emmy and has been nominated for an Oscar and a

Grammy. Yet he can still travel unrecognized -- or at least be mistaken

for Bill Murray.

Unlike others who have graduated from "Saturday Night Live" to

success in films, Aykroyd is such a gifted sketch actor that he is better

known for the characters he has played than as a comedic personality.

Over the years, he's preferred to let his work speak for him, keeping a

low profile in the media, while some of his "SNL" contemporaries -

including a few who followed years later - achieved major stardom, burned

out and are planning their comebacks.

Despite his 27 movies -- some, like "Ghostbusters" and "Driving

Miss Daisy," were blockbuster hits -- Aykroyd will be forever linked to

his days on "SNL" His legendary moments range from the Weekend Update

newscasts to send-ups of Nixon, Carter, Tom Snyder and Julia Child to

skits featuring the Blues Brothers, Two Wild and Crazy Guys, Killer Bees

and the Coneheads. He also divas one half of the show's most outrageous

comedy duo: Aykroyd and his best friend, John Belushi, were lauded as the

Lennon and McCartney of comedy.

Together, Aykroyd and Belushi ventured into movies with "1941"

and "Neighbors." Two characters they created for "SNL, "Jake and Elwood

Blues, moved to the big screen in the monster-budgeted "Blues Brothers,"

in which dozens of police cars and an entire shopping mall were

demolished. They also recorded best-selling albums and performed to

sold-out audiences, even opening for the Rolling Stones and getting a

Grammy nomination for best new artists. As Elwood, Aykroyd played a

convincing harp and did one of the funniest and stiffest shuffles ever

seen onstage.

When Belushi died of a drug overdose in 1982, Aykroyd began a

solo career. He thrived, landing starring roles opposite Eddie Murphy in

"Trading Places," Walter Matthau in "The Couch Trip" and Kim Basinger in

"My Stepmother Is an Alien." He co-wrote "Ghostbusters," in which he

starred with Harold Ramis and Bill Murray. It was the number-one-grossing

comedy until it was topped in 1990 by "Home Alone." Aykroyd also earned

good reviews for his re-creation of the role of Sergeant Joe Friday in

the movie version of "Dragnet," another of his script-writing efforts.

Just when it seemed as if Aykroyd were destined to a career of

sweet if often silly comedies, he was a surprising casting choice as the

worried son in "Driving Miss Daisy," directed by Bruce Beresford. The

film won the 1990 Oscar for best picture, and Aykroyd earned a best

supporting actor nomination. That was followed by a role in "Sneakers"

with Robert Redford and Sidney Poitier. Next, Sir Richard Attenborough

cast him in "Chaplin," which he finished shortly before launching into

"The Coneheads" with his boss at "SNL," Lorne Michaels.

Aykroyd was born in Ottawa, Canada into a practical-joking,

movie-watching family in which seances were typical Saturday night

entertainment. He attended Catholic schools and over the years worked at

jobs that pointed many places other than show business. He drove mail

trucks, load-tested runways for jumbo jets, surveyed roads and wrote a

manual for penitentiary guards.

At Carleton University in Ottawa he became involved in a theater

group, the first of several comedy ensembles he joined. He was soon

appearing on Canadian TV in what he describes as a hip precursor to

"Rowan and Martin's Laugh-in," which led to a stint with the Second City

troupe in Toronto with co-stars Gilda Radner and John Candy. While in

Toronto he met Belushi, then a performer with Second City in Chicago.

Like Belushi, Aykroyd had his wild years, though he says he

preferred wine and beer to the heavy drugs that brought down Belushi. He

loved hanging out with friends, and he opened the Blues Bar in lower

Manhattan for late-night or, often, all-night parties.

Now his life is far quieter. On the set of "Doctor Detroit,"

Aykroyd fell in love with his co-star, Donna Dixon (who appeared in

"Wayne's World"). They married and have a daughter, Danielle, now three.

The family spends as much time as possible at its 70-acre lakeside farm

in Ontario. When the Aykroyds are there, the serenity of the Canadian

nights is occasionally broken by the sound of one of Aykroyd's several

modified Harley-Davidsons; he's an obsessed biker. He planned to head

back to Canada as soon as "The Coneheads" wrapped.

Contributing Editor David Sheff, whose last tete-a-tete in these

pages was with musician-philosopher Frank Zappa, took on the tete-a-cone.

Here is Sheg's report: "When I first met Aykroyd, in 1979, he had

recently completed 'The Blues Brothers.' He was a less-than-eager

interview subject, seemingly uncomfortable talking about most aspects of

his life. In the years since then, everything seems to have changed, not

only in his life and career but in him. For this interview he was

forthcoming and at ease. Often, he came across as overly earnest --

almost corny -- as if time had taken the rebel out of him. But there's no

doubt he seemed genuinely happier.

"I met with Aykroyd on the set of 'The Coneheads,' which was

being filmed in Los Angeles. He was in costume for much of the interview,

and I found it disconcerting, if somehow appropriate, to look up at him

during impassioned conversations and realize I was talking with a

Conehead."

PLAYBOY: Is it a surprise to find yourself back en cone after all these

years?

AYKROYD: Yeah. I thought we had put away the cones for good. But Lorne

[Michaels], now a successful movie producer after Wayne's World,

thought it was the most logical project.

PLAYBOY: What originally inspired the Coneheads?

AYKROYD: I was looking at the TV and thinking, If people's heads were

like this [he presses the sides of his skull together], they

could fill the screen a little more.

PLAYBOY: Has the cone changed over the years?

AYKROYD: The original was just a cheap piece of plastic that was glued to

the forehead and around the top of the ears. This cone is done

by a top-notch, professional makeup guy, David Miller, who did

the Freddy Krueger makeup.

PLAYBOY: It's a little unsettling.

AYKROYD: Yeah, it kind of frightens small children.

PLAYBOY: Is it uncomfortable?

AYKROYD: No, but I bump my head a lot because I forget how tall I am. It

adds six inches. There are two moments of discomfort when they

put it on. I imagine it's like being decapitated or getting a

lethal injection: You feel a pinprick and then it's all over.

With this you feel two applications of cold glue -- to your neck

and forehead -- and that's it. It's comfortable enough for me to

take naps in. Actually, it's like wearing a dunce cap all day,

which former teachers of mine might find fitting.

PLAYBOY: Since Wayne's World, which also started as a skit on Saturday

Night Live, was such a success, do you feel extra pressure with

The Coneheads?

AYKROYD: Oh, yeah. They're going to be sitting there with their arms

folded, tapping their feet, waiting for this one to bomb. But

that can't really affect what I'm doing here. The writing's

good. The story's great. I'm reasonably confident because I know

people want to laugh. It's time for laughter.

PLAYBOY: Why now?

AYKROYD: People always need laughter. It's well known that laughter

produces some kind of endocrinologic response that cures and is

otherwise good for people. The more the better.

PLAYBOY: Are hard times -- recessions, ethnic wars abroad, inner-city

tensions -- fertile times for comedy?

AYKROYD: There was a profusion of light-hearted movies in the Thirties,

all meant to get people's minds off the Depression, but I don't

think filmmakers consciously make movies to take people's minds

off hard times.

PLAYBOY: You're working with several of your former co-stars from

Saturday Night Live. Do you feel like you're in a time warp?

AYKROYD: Having Jane [Curtin] walk in and -- bang -- go right into the

character, just where we left off, is great. It's like it never

stopped. Some of us have put on weight or gotten gray, but it's

better. The skills increase over time.

PLAYBOY: What about your sense of humor?

AYKROYD: It's sort of the same. We're still into shock humor and we still

deal with the absurd.

PLAYBOY: Has what's funny changed?

AYKROYD: Some things are always going to make people laugh. In

Neanderthal times, people probably laughed at jokes about

burning themselves with fire and how funny their mates looked.

We're laughing at the same things today -- the things in our

lives, human behavior. We laugh at toilet jokes, at shock. Then

you get into the Nineties and you have guys like Sam Kinison,

God rest his soul, and Andrew Dice Clay -- the abrasive and

caustic humorists. That's really what has changed. It's like

everything is through the top now and we have people out there

who are striving to shock. I don't know what the year 2000 will

bring. Maybe guys will be chopping off their fingers.

PLAYBOY: Are there places where lines should be drawn?

AYKROYD: I'm not much into bathroom humor unless it is really well done.

We did a skit called the Widettes, in which the characters had

huge haunches. Once, we hung toilet paper out of the backs of

their pants. That was justified. I have never been into

gratuitous sex or swearing, though; it has to have a purpose.

PLAYBOY: How about the meanness -- you mentioned Clay and Kinison?

AYKROYD: It makes me laugh, but I don't do that kind of thing.

PLAYBOY: Do you find some of it in questionable taste?

AYKROYD: Yeah, and I don't really like vulgar stuff. People may call

liquefying a bass vulgar, but I don't think so.

PLAYBOY: You're referring to the Bass-o-matic routine you did on Saturday

Night Live.

AYKROYD: Yeah. But to people who think that liquefying a bass is

offensive, I have to point out that this woman in Canada, sort

of our Julia Child, uses the blender to make fish soup -- bones,

head and all.

PLAYBOY: Are there certain targets that should be off-limits?

AYKROYD: I don't think the weak, oppressed, poverty-stricken and

handicapped should be targets, unless they do it themselves, and

then I'm ready to laugh. There are things I wouldn't do, but it

depends on the writing. If it's good, I'll do just about

anything. You're talking to the man who had his pants down below

his hips and who then put a pencil between his cheeks -- on

national television.

PLAYBOY: What was the occasion?

AYKROYD: I was playing a refrigerator repairman on Saturday Night Live.

It was a nerd sketch -- the Lupners -- with Billy [Murray] and

Gilda [Radner]. I came in as the refrigerator repairman and the

nerds were breaking up watching me move the fridge because I was

one of those guys who wear their belts very low. I just got

down like this [he demonstrates] and did the character, and when

I put the pencil in, I rested it -- against broadcast standards'

request -- right there between the cheeks. Now, people may argue

that was as vulgar and cheap as you can get, and at first I

didn't want to do it. Lorne talked me into it. The audience

howled. It was a magic moment You have to watch the tape to see

how subtle that insertion was.

PLAYBOY: How tough was it to make the move from TV to films?

AYKROYD: Movies are a whole other canvas, like working with acrylics

compared with modeling clay. TV is like skywriting and movies

are more like setting up dominoes and letting them fall.

PLAYBOY: Is it frustrating to work in movies where you have less control

over the material?

AYKROYD: The frustration is that good ideas are put into a blender. There

are so many factors -- writers, producers, directors, actors and

others -- that make or break what might be a great idea. We go

into these projects with the best intentions, willing to do the

best work possible. You just never know how they're going to

turn out. You can do only so much, and so much of movies is out

of your control. On the other hand, when it works there's

nothing else like it.

PLAYBOY: It seemed to work for you in Driving Miss Daisy. Many people

thought you were an unusual choice for that role.

AYKROYD: A friend saw the play and said the part was good for me, so when

I heard they were making the movie, I had my agent call. I sat

down with the producer, Richard Zanuck, and told him I'd like to

do it. I was thrilled when I got it.

PLAYBOY: Were you consciously trying to get away from your usual comedic

roles?

AYKROYD: Yeah, I wanted a little variety in the career.

PLAYBOY: What was your reaction to the Academy Award nomination?

AYKROYD: Obviously it was very gratifying. It sort of legitimized my

efforts.

PLAYBOY: Were you surprised?

AYKROYD: Oh, yeah. But I knew I wasn't going to win because I had seen

Glory. I knew Denzel [Washington's] performance was the one.

But it was cool. I still went to the show. Morgan Freeman and I

hopped up and down like excited little kids when Driving Miss

Daisy won Best Picture. If I never do another dramatic part, I

can look back and say I was in the best picture of 1989.

PLAYBOY: After doing all those comedies, did you have any trouble playing

a more serious part?

AYKROYD: No. The acting is different but it's still the same. The hardest

part is getting producers and directors to consider you when

they already think of you as a comic actor. For me it has less

to do with what kind of movie it is than who I'm working with.

In Driving Miss Daisy, I got a chance to work with Jessica Tandy

and Morgan Freeman. More recently I did Sneakers with Robert

Redford and Sidney Poitier. By now I've worked with some of the

best. Walter Matthau in The Couch Trip, Bill Murray in

Ghostbusters, Eddie Murphy in Trading Places, Tom Hanks in

Dragnet.

PLAYBOY: You wrote Dragnet, one of your many movies featuring cops and

robbers. From where does the fascination with crime come?

AYKROYD: I like to explore adventures and events that I wouldn't normally

be part of. I'm an armchair quarterback. I don't really have to

live that life, but I can act it.

PLAYBOY: You even studied criminology.

AYKROYD: Yeah, in college. I gravitated immediately to sociology and

abnormal and deviate psych.

PLAYBOY: Ever think of being a cop?

AYKROYD: I couldn't be a cop because I have two differently colored eyes

and webbed feet. It means I'm a genetic mutant and would

probably be rejected for any kind of service.

PLAYBOY: So what's behind your interest?

AYKROYD: I was curious about what makes a person turn from the straight

and narrow to a life of crime. And the other side of it is law

enforcement. I have a lot of friends who are cops.

PLAYBOY: After you ruled out police work, what led you to acting?

AYKROYD: I had done plays in college in Ottawa. I was kind of hoping

something would come up so I wouldn't have to go through and get

the degree. When I was seventeen, Valerie Bromfield, who was a

writer and performer in Ottawa, got me started doing a cable

show. She had met Lorne Michaels, who was doing a show called

the Hart and Lorne Terrific Hour, sort of like the Canadian

Rowan and Martin, but earlier. They had long hair and they were

the only hip thing Canada had seen. I eventually became involved

in that. Then I went back to school until Valerie dragged me out

and moved me to Toronto for good. We formed a comedy team doing

Mike Nichols and Elaine May -- type bits. We used to go on after

a transvestite named Pascal. He/she opened for us. This led to

Second City.

PLAYBOY: Where you worked with Gilda Radner for the first time.

AYKROYD: Yeah. Gilda was already breaking hearts left and right. All the

guys loved her. You know how Bill Murray would pick her up and

twirl her around his head? I felt that way about Gilda.

PLAYBOY: Huh?<

AYKROYD: I would express it differently, but I understood it when Billy

would pick her up and twirl her around and begin biting her.

PLAYBOY: Did you remain friends with her after SNL?

AYKROYD: We all kind of lost touch with Gilda. She married Gene Wilder

and built a life with him. Our paths didn't intersect for many

years, until I saw her at a party at Laraine Newman's house one

year before she died. Everyone there was around her like filings

around a magnet. But we had a lot of years together at Second

City and then on Saturday Night.

PLAYBOY: How did you get the job on Saturday Night Live?

AYKROYD: John Candy and I were both at Second City and we took a drive to

Pasadena in his Mercury Cougar to be at a dinner-theater show

that Second City was opening. It took thirty-eight hours, and as

soon as we arrived, Lorne Michaels called and asked me to come

back for an audition. I flew to New York. People were lined up

everywhere. I thought, I'm not prepared for this, this is crazy.

But I went in and Lorne put me behind a desk to do a news

report, a la Weekend Update. That was 1974. I was with SNL

through 1979. I've often thought, If I ever get a tattoo, it's

going to be a little TV set with SNL 75-79. It's like if you

spend time on the USS Guadalcanal and get a patch.

PLAYBOY: Have you ever heard from the subjects you skewered on SNL?

AYKROYD: No, though I was in an elevator with Tom Snyder. I don't think

he recognized me. I hope he didn't. I tried to disguise myself.

PLAYBOY: What about Jimmy Carter?

AYKROYD: I performed with Chevy Chase at the Carter inaugural. Chevy

played the chief justice swearing in Carter. I did Carter. There

we were, at the Kennedy Center, with all the people who move the

machinery of government sitting there. And I came out onstage

in a jeans jacket and the traditional inaugural stovepipe hat,

and Chevy swore me in using the Crest toothpaste oral dentifrice

pledge. Later we found out that at the moment Chevy and I

stepped onstage, Carter was called away. He was told that there

was an important Department of Defense briefing, but I'm sure

they just wanted to get him out of there.

PLAYBOY: But he probably had to approve your appearance in the first

place, didn't he?

AYKROYD: No. He asked Chevy to come and do Ford. Chevy snuck me in.

PLAYBOY: Who was your favorite subject to impersonate?

AYKROYD: Nixon. I mean, he was just rich. Reagan was good, too.

Republicans are much richer to do. Ross Perot, too. What a

dream for an impressionist. That voice, that look.

PLAYBOY: Have you tried doing Clinton or Gore?

AYKROYD: Clinton is Phil Hartman's territory. I could look at Gore. There

are a few things there -- the posture, the stance, the pace. But

for me there's nothing like good old Nixon.

PLAYBOY: Do you vote for the candidate who would be the best target for

parody?

AYKROYD: As a Canadian citizen I don't have a vote in this country. My

wife has the vote in the family and I try to convince her, but

she votes the way she wants.

PLAYBOY: How would you describe your political bent?

AYKROYD: In Canada I would probably be classified as a far-left liberal,

anti-socialist, free enterprise capitalist.

PLAYBOY: Where do you stand on the Quebec secession?

AYKROYD: I will stand behind Quebec. Whatever the citizens of that

beautiful part of the world do, I will stand behind them. If

they choose to separate from the rest of Canada, I will support

them, with reluctance, because I don't want to see my nation

splinter. My mother is full French Canadian and I'm half

French-Canadian. She feels the same way: sad, sorry things

haven't been worked out. But the problem there dates back to

when the English seized the nation and called it English Canada.

Quebec license plates read JE ME SOUVIENS, which means, "I

remember." Basically it means, "I remember how I was fucked over

by the English." They remember that they are really French and a

separate cultural entity.

PLAYBOY: Did you begin your training as a performer in Canada?

AYKROYD: Yeah. My parents sent me to drama and improv classes when I was

twelve. I was distracted by theater and the arts and acting all

the way through. Other fathers made their kids toy guns; my

father carved me a little wooden microphone, painted black on

the top, with a rope for a cord.

PLAYBOY: Is a sense of humor hereditary?

AYKROYD: In my case. My grandmother on my father's side was always

writing verse and poetry and couplets and funny rhymes with

little lessons in them. Then there was my grandfather, who had a

nice, wry sense of humor. On my mother's side of the family

there was always music around, someone banging on the piano,

singing a song.

PLAYBOY: In the movie The Blues Brothers you poke fun at Catholicism. Was

your family religious?

AYKROYD: Yeah, I was an altar boy.

PLAYBOY: Did your parents cringe at your irreverence?

AYKROYD: Not really. They know it's true. And I'm not slamming religion.

I'm not what you would call a fervent practicing Catholic, but I

do slip in the back door of church a couple times a year.

PLAYBOY: Why?

AYKROYD: I like the music. I have a faith of a kind. I'm not a born-again

Christian, but I have some faith. I think that God is in and

around all of us, in everything, and thus we're all connected. I

have always believed that. I feel a link to the squirrels

outside, and that's what God is to me. If He introduces Himself

to me, sits me down and tells me something different, then I

will reconsider my feelings.

PLAYBOY: It sounds as if you had a nice, cheery childhood, not the

tormented childhood many comics endure.

AYKROYD: My parents and grandparents and my home life were warm and

beautiful, with probably the normal deficiencies. My mother and

father both worked. I went to work at fourteen because I had a

lifestyle to maintain. I wanted to be out in the world

exploring, I wanted to have money for dances and movies. My

father earned a government salary and my mother had a salary

barely enough to keep the car, the house, the groceries going.

No way I could lie around and wait for a BMW.

PLAYBOY: Were you exposed to big-name comics when you were young?

AYKROYD: Yeah. I appreciated all the great practitioners of the craft --

Jack Benny, George Burns. Bob Hope and Bing Crosby in those road

pictures. Desi Arnaz, one of the great, great comedians; Lucille

Ball, amazing timing. Carol Burnett, Carl Reiner, Sid Caesar,

Morey Amsterdam -- all the classics -- Dick Van Dyke and Mary

Tyler Moore on the early show. Red Skelton. Jackie Gleason and

Art Carney in The Honeymooners. The work Walter Matthau and Jack

Lemmon did together. Of course, Bob Newhart, Tim Conway and

Harvey Korman. I grew up with these people.

PLAYBOY: Were you a Charlie Chaplin fan? Did that weigh in your decision

to take a role in Chaplin?

AYKROYD: Not really. I saw all his movies when I was a kid. My dad would

rent them and show them on a bedsheet in the basement. But I

preferred the Keystone Cops, Laurel and Hardy, and Buster

Keaton. I appreciate Chaplin more after making the movie. It was

a fun movie to make and it was incredible to work with Sir

Richard Attenborough, who directed it. That one just came to me.

I was asked to read for the part.

PLAYBOY: Is it more interesting for you when you write the script, too?

AYKROYD: I love writing scripts. But it's different. It is also great to

have a truly good script written by someone else and to come in

and just do the job as an actor.

PLAYBOY: Were you writing most of your stuff back in the SNL days?

AYKROYD: I had nothing to do with many of the great pieces. James Downey,

who was a producer of the show, wrote the Two Wild and Crazy

Guys skit, though Steve [Martin] and I came up with the idea.

Steve came up with his continental guy, which I fused with my

Czech architect. It was like dealing with split personalities.

Julia Child cutting her hand and bleeding everywhere was written

by Al Franken and Tom Davis. Belushi wrote a great piece for me

about the Swiss army gun. Instead of spoons and blades, it had

blowtorches and bazookas and all. I wrote some pieces with Alan

Zweibel, who went on to produce It's Garry Shandling's Show and

who wrote Dragnet with me. We did The Headcheese Cash Machine

sketch, in which all U.S. currency has been converted to

headcheese.

PLAYBOY: Were there limits to how far you could go on Saturday Night?

AYKROYD: They didn't want me to put the pencil between my cheeks. We had

to fight over some things. Placenta Helper was a big fight.

PLAYBOY: Remind us.

AYKROYD: It was like Hamburger Helper for placentas. There was this New

Age, Greening of America sort of concept where the husband would

eat the placenta for all kinds of strange reasons. Franken and

Davis wrote it but it never got on the air. But there weren't

too many fights. Some of the Weekend Update fights were pretty

extensive. Lorne would fight for us every time. If a writer

believed in something and wouldn't give up, Lorne would fight to

the wall.

PLAYBOY: Did he usually win?

AYKROYD: Eighty percent of the time. The rest of the time they drew the

line. I think we had to fight to say 'Jane, you ignorant slut"

when we were doing our point-counterpoint thing. The word slut

was the problem. Another thing we did was have the audience send

in joints. We did a bit saying, "Pot is bad, so send your joints

to us." And people sent us joints.

PLAYBOY: How much pot came in?

AYKROYD: Many envelopes. Some good, some not so hot, some homegrown, some

real good. A lot of pot was sent in. And dollars. Another time

we asked for dollars. I think it's illegal to get money. I think

Soupy Sales did it once and was chastised for it.

PLAYBOY: What do you think of the current SNL?

AYKROYD: I'm a big, big fan. I watch whenever I don't fall asleep.

PLAYBOY: Does it amaze you that the show is still going?

AYKROYD: Definitely. It was touch and go there for a while because they

thought it wasn't going to succeed after everybody left.

PLAYBOY: You didn't go back to guest on the show for years. What took so

long?

AYKROYD: The fact of the matter is it was emotionally trying for me to go

back to 8H.

PLAYBOY: 8H?

AYKROYD: Yeah, 8H, the studio at NBC where we made Saturday Night. I had

big memories of John. I remember all kinds of things -- him

being wheeled down the halls when he twisted his knee after

doing the twist offstage and then whirling out, taking a bow and

heading right into the orchestra pit. Things like that. I still

see him in the halls there. I go through such emotion. I guess I

was a little afraid of the feelings that would well up. I was

afraid I'd go up there and get maudlin.

PLAYBOY: When did you first work together?

AYKROYD: I came down on my bike from Toronto to Manhattan and did a guest

spot on the National Lampoon Radio record that he was working

on. I was a drummer on a Helen Reddy parody. We started to work

together in earnest on Saturday Night.

PLAYBOY: How would you characterize the relationship?

AYKROYD: We just immediately clicked and became fast friends. We brought

each other different sensibilities. He introduced me to the

Allman Brothers and Bad Company and heavy metal and I introduced

him to old blues. He took me under his wing. He had the capacity

to sweep you along into his rhythm. With John you just kind of

jumped onto the inner tube and took a ride. John and his wife,

Judy, let me stay in their apartment. I slept at the foot of

their bed for almost a year, because I was commuting from Canada

when I wasn't sure whether I was going to move to New York. They

were sort of like my aunt and uncle.

PLAYBOY: Can you describe what each of you brought to the collaboration?

AYKROYD: It's one of those mystery things of instant chemistry. The two

of us together had a good look. Both of us would play straight

and both of us would play support. I don't know. It was just one

of those things.

PLAYBOY: Somebody called you and John the Lennon and McCartney of comedy.

AYKROYD: For a while I guess we were. Elaine May and Mike Nichols and Art

Carney and Jackie Gleason -- there are a lot of great teams

around. We had our moment.

PLAYBOY: Did you have a favorite moment together?

AYKROYD: On the show doing the Nixon and Kissinger thing. I think Richard

and Henry bonded us.

PLAYBOY: What do you remember about hearing the news that he had died?

AYKROYD: Well, you know, it was over for me very quickly. It was really

over for me in the first minute I realized that he was gone.

PLAYBOY: Had you tried to intervene when it was clear he was having

problems with drugs?

AYKROYD: We all tried to talk to him. It was hard because he refused help

from people who loved him. In retrospect I see that the Betty

Ford confrontation technique is about the only way we could have

done anything, but if we had used it, I can see him getting mad

at all of us and storming out the door and disappearing for

days. We would have literally had to handcuff him, and I think

that's what we should have done. He made progress the summer

before he died. He was completely off the powders. But he got

frustrated.

PLAYBOY: By what?

AYKROYD: The business. And there were people around to hand him anything

he wanted.

PLAYBOY: Do you blame those people?

AYKROYD: Well, you can be sure that with all those people, it was John

who was running their lives, not the other way around. He was

having them come and go as he wanted. He was the captain of his

own ship. He was at the helm. Or maybe he wasn't, and that's the

trouble. He was downstairs in the galley and there was no one

at the helm. So I can look back only with great fondness and a

little anger. But we had eight good, rich, fulfilling years

together, creatively and in terms of a friendship.

PLAYBOY: Did you expect something like that to happen?

AYKROYD: He said he was heading for an early grave. He was always

alluding to that. But that's no reason why we should have

accepted it.

PLAYBOY: It sounds as if you feel somewhat guilty.

AYKROYD: It's very hard when someone doesn't want to change, or if they

want to change and their will is weak. But I regret that I

wasn't stronger, and in a way I do feel a little bit of guilt

for letting him slip through my fingers. But there were times

when I did try and there were times when I was effective. Times

when he did listen to me. I feel good about the occasions when I

was able to help and bad about the occasions when I slipped up.

PLAYBOY: Did you hear about his death from Judy?

AYKROYD: No. I told Judy. I got the call from [our manager] Bernie

Brillstein. He called me at the office in New York. It was a

beautiful March day and absolutely spectacular in New York. The

weather was warm and clear and the streets were full of people

enjoying the sunshine. I'll never forget that walk from 150

Fifth Avenue to Morton Street to Judy's house, because I was

thinking, I can't get in a cab, I've got to keep walking.

Richard Pryor described it when he was burned: He just kept

running to stay alive. He knew if he stopped he was going to

die. I had that same desperation. I knew if I stopped, it was

going to get me, so I just had to walk and get there before Judy

heard it on the radio. I managed to get there and I told her.

"He's dying" is all I said. And that was the most painful part

for me. After John, Gilda died. I guess the only question is,

Who's next? Gilda and John are gone, and gone before the close

of a millennium, which is kind of frightening, because it didn't

have to happen. Her cancer should have been detected much

earlier. And John did not have to die from that speedball,

because he should have just left L.A. He shouldn't have been

hanging around with those people. He should never have gotten to

the point where he was fucking with that shit.

PLAYBOY: Did what happened to John affect your views on drugs?

AYKROYD: As I've always said, we're born in this pure vessel and it's our

choice what we want to do with it. There are a lot of pleasures

out there. Everyone has to decide. I don't crusade against

drugs. I have a resistance to that. I suppose I say, Just be

moderate, just be careful. Look at the destruction they've

caused. John was a shell that washed up on a beach in the tidal

wave of the billion-dollar cocaine industry. It's a big

business.

PLAYBOY: Could you have gone down a path similar to John's?

AYKROYD: I was never into the powders. Maybe the difference was this: In

a sense, of the two of us, John seemed to have the harder

exterior, a more macho, male, harder thing going. In reality,

though, deep down, I'm the boulder, he was the softy. I might

have been the one who was more accommodating and more open when

you'd meet us, but I'm also the one with the controlled edge and

the hardness. He was the soft innocent. And my edge and coldness

kept me from those pursuits, whereas his softness and innocence

made him vulnerable. To hide it, to close that up, he used drugs

-- as armor.

PLAYBOY: Even though John is dead, we've heard the Blues Brothers are

making a comeback. Why?

AYKROYD: Well, after John died I thought that would be it. But right

after, I met this friend, Isaac Tigrett, who had lost two

brothers to tragic circumstances, and his grief was so much

bigger than mine could ever be. He helped me get over John's

death. We became partners in the Hard Rock Cafe enterprise east

of the Mississippi. He ran it, built several restaurants, went

public and sold the company for a hundred million English

pounds. So I'm out of that, but every time we opened a Hard Rock

Cafe, the Blues Brothers band came together. The original band.

For a while our co-singer was Sam Moore of Sam and Dave. Then

the band asked if we would license them the name so they could

tour. Judy and I said, "Go for it"; we get a small percentage of

the take. I go out and play the harp sometimes. We do Soul Man

and Knock on Wood. We rip the house apart.

PLAYBOY: How do you rate your musical abilities?

AYKROYD: I'm a great emcee -- front man and I can move onstage. It's

funny and exciting to see a man of two hundred-plus pounds

moving in such a way that it looks like he knows reasonably well

where he's going and he's not going to hurt people.

PLAYBOY: What are your musical tastes these days?

AYKROYD: I listen a lot. My favorites are the Black Crowes, Robert Cray,

Bonnie Raitt, Stevie Ray and Jimmy Vaughan, Kim Wilson and the

Thunderbirds. There's also a new band called Blues Traveler

with an amazing new young harmonica player named John Popper.

PLAYBOY: Might there be another Blues Brothers movie?

AYKROYD: I'm working on a story with John Landis, who directed the

original. We're going to try to bring back everybody from the

first movie. We have to convince the studio. The walls of

Universal are still stained from the first Blues Brothers movie.

PLAYBOY: Stained? Didn't Universal make money on that?

AYKROYD: Not really, because it cost so much. They made their money back,

but it was traumatic getting the movie made. It was an enormous

production. John was out of control.

PLAYBOY: You've often been criticized for creating movies with runaway

budgets.

AYKROYD: We are always criticized for costs -- for 1941, Ghostbusters,

Blues Brothers -- but that money doesn't go into the pockets of

the actors and directors, it goes into the pockets of labor.

PLAYBOY: And special effects and wrecked cars....

AYKROYD: The major expense of Blues Brothers was not the seventy police

cars we bought from the Chicago Police Department. We paid only

$700 each for them. The major expense was labor, so that's good,

it gets people working, and why shouldn't the profits of the

mega-corporations be reinvested in the trades of this industry?

If I write a big show and it costs a lot of money, I make no

apologies. I'd be a wealthier man today and a better businessman

if I sat down and wrote small movies that cost little and

brought in lots.

PLAYBOY: Will you continue to make sequels -- whether based on the Blues

Brothers, Ghostbusters, Coneheads or others?

AYKROYD: As long as there is something new to do with them and it's

enjoyable. It's kind of nice to have built-in franchises. The

one I don't think we'll necessarily further exploit is

Ghostbusters. It looks like that's about had its run.

PLAYBOY: Because Ghostbusters II did poorly?

AYKROYD: Yeah. It opened and Batman opened the next weekend and wiped us

out that summer. Although we made a good movie, it just wasn't

as commercially successful as everybody thought it would be. If

I could get that team together, it would be a real dream,

because I think there's a great story to be told. But it won't

be for a while. By the way, I heard a great ghost story about an

old Manhattan hotel, the Sheraton, that is now the Chinese

consulate on 42nd Street on the West Side. We were shooting on

the fifth floor in a banquet room. I was outside having a smoke

and I saw this guy go down the hall in an Air Force jacket with

master sergeant stripes. I asked him what was up. He told me he

was an electronic-countermeasures technician who installs ECM

packs on F-16s and F-106s and all that. He told me that his

father worked in the building and then he mentioned, "We can't

keep guards." When I asked what he meant, he said they had gone

through five security guards. They would come running

downstairs, yelling, "You can keep your job." They finally

questioned one, who said, "I was making my rounds and I saw

something come through a wall." When the man was asked what he

had seen, he said, "It was a man's head and shoulders. He was

wearing red." So this guy and his dad and brother go up there to

check it out. They were walking on the fifth floor and they saw

something go across the hall: a guy wearing a red chef's hat and

holding a knife and fork. They followed him into the kitchen

and he disappeared into the mashed-potato mixer. He said they

researched the employee records of the hotel and found that a

week after it had closed, the roast beef chef, who had been

there for fifteen years or something, went to a bar around the

corner and drank himself to death. His presence is still around.

PLAYBOY: Do you believe that story?

AYKROYD: It's a perfect example of a ghost story I can place credence in

because it was unsolicited. Now that the Chinese consulate is

there, I've wanted to talk to someone in charge and ask if there

have been any experiences with the presence.

PLAYBOY: Have you ever had a personal experience with a presence?

AYKROYD: My wife and I bought Mama Cass' old house in Hollywood. It is

where Cream, John Lennon and Harry Nillson used to hang out.

Ringo owned it for a while. California Dreamin' was rehearsed

there. We have a presence in that house. A psychic came in and

told us that some guy apparently died of a drug overdose in the

living room. My wife and I told a friend of ours about it and he

turned ashen and gasped. He said, "I know about that." It

happened just as the psychic said. It was something that had

been hushed up.

PLAYBOY: You called a psychic?

AYKROYD: We had to. The maid wouldn't go upstairs. Also, my mother

experienced some stuff' there and some friends heard the piano

playing and then heard footsteps and doors closing. When the

psychic said she couldn't deal with it, my wife went to more

traditional methods -- religion -- to try to get rid of it. But

we think it's still there because recently the other maid went

upstairs and a door slammed. Another time I was alone in the

house in bed and I felt the mattress depress behind me like

something was getting into bed. You know what my reaction was? I

didn't hop up. I wiggled my rump right up next to it. I thought,

If you can like me this much, you're going to feel me right

next to you.

PLAYBOY: Did you believe in ghosts as a child?

AYKROYD: Of course. They had seances at the old family farm where I grew

up. My mother witnessed an apparition. I once saw some lights I

couldn't explain. My father was a psychic researcher, so it was

really passed down to me.

PLAYBOY: It seems Ghostbusters is your idea of a documentary, not

fiction. Are you pulling our leg?

AYKROYD: Definitely not. The other day I read that Harold Ramis, my

colleague in Ghostbusters, said he doesn't believe in ghosts!

PLAYBOY: And that surprises you?

AYKROYD: Yes, because he is a very smart person. I'm going to bring him

up to Dudley Town, Massachusetts and scare the shit out of him

sometime. I'll take him to the most haunted place on earth.

He's my man. He's going. I can't believe he offhandedly says he

doesn't believe in ghosts when it's a reality of life on this

planet. He's going to get spanked for that.

PLAYBOY: Don't you require more proof of ghosts than those vague

experiences?

AYKROYD: Sure. I'm a skeptic. If somebody tells me a ghost story, I want

proof. I want to know if he or she was smoking or drinking. In

eighty percent of the cases I've inquired about, you can put a

name to the presence, a human name. You know why they're there.

PLAYBOY: Why are they there?

AYKROYD: They died in an unfulfilling and unsatisfied way and they are

lingering here in this world for something that they'll never

have. And it's very simple. Very simple.

PLAYBOY: Frankly, Ramis' view isn't much of a surprise to us.

AYKROYD: But Harold's such a brilliant philosopher. He knows that the

empirical scientific world is not all there is. Maybe that's all

he sees. I just can't believe that he means it. He's such a

practical man, I suppose.

PLAYBOY: Did your experiences with ghosts inspire Ghostbusters?

AYKROYD: Sure, and old ghost movies. Bob Hope, the Bowery Boys, the Marx

Brothers all did ghost routines. Ghosts were a big part of humor

in the Thirties and Forties. Ghostbusters grew out of those as

well as my commitment to and ongoing support of the American

Society for Psychic Research.

PLAYBOY: Have you ever not believed?

AYKROYD: No. There is just too much literature, too much research being

done, too much evidence.

PLAYBOY: You have no doubts?

AYKROYD: None.

PLAYBOY: Are you ever nervous talking about it in public?

AYKROYD: Not really. Because I got all this legitimization from my

parents on it. It's a fascinating area of study.

PLAYBOY: Has there ever been an advisor to you -- a publicist or manager

-- who said, "Listen Dan, this is not the kind of stuff you want

to talk about"?

AYKROYD: No, not really. Ghosts are part of the general lexicon. Most

people know they exist.

PLAYBOY: What is the closest thing to a real Ghostbuster today?

AYKROYD: There are paranormal scientists who work in the field of'

telepathy and ESP. There are people who have equipment to detect

ghosts.

PLAYBOY: What type of equipment?

AYKROYD: Highly sensitive photo equipment and sound equipment that can

detect presences. A guy I know says that he gets seventy-five

percent of his referrals from religious people.

PLAYBOY: Don't priests feel that it's heresy to mess with those forces?

AYKROYD: But a parish family might have a problem with their house. The

priest goes over and gives a blessing, spreads around some salt,

lights a candle. That doesn't work and ultimately....

PLAYBOY: Who you gonna call?

AYKROYD: Right. The priest refers it to a professional.

PLAYBOY: How about UFOs?

AYKROYD: There is no question about UFOs. There are photos, videos,

recordings. The military knows about them.

PLAYBOY: Have you seen UFOs?

AYKROYD: I've had two vivid experiences. One time the lights were green

S-shaped cubes, like two S's following each other, like two

little sea horses. They were at the top of the stairs in the old

farmhouse in Canada. I was with a friend. We both saw them.

PLAYBOY: Were you straight?

AYKROYD: We were probably not straight, which immediately discounts me by

my own rules, but I know what I saw. My mother saw an apparition

there once; that's what led to the seances they had at our

house. I saw the other UFO on Martha's Vineyard at my hilltop

estate 272 feet above the ocean. It was about three in the

morning. I went outside to take a leak off the balcony and I saw

it coming from the far upper-right-hand corner of my vision: two

objects, around 150,000 feet high. They were perfect circles

flying in tandem. They did a beautiful zigzag. I screamed at my

wife and my friend's girlfriend to come out. They did and the

three of us saw these objects do a beautiful zigzag, and pow!

Gone across the sky.

PLAYBOY: The problem with all the anecdotal evidence you have is that

anecdotal evidence can prove anything. There can be all kinds

of explanations for lights in the sky.

AYKROYD: Forget anecdotes. We're talking about ghosts, UFOs. There's

physical, recorded evidence. This woman in Massachusetts, every

time she picks up a camera and takes a picture, ethereal images

appear. She shot some super-H film that was silent and then

played it backward and there were ethereal voices on it. It made

my hair stand right up on end when I heard it. UFOs? There's a

famous photo that people have proved is not a hoax.

PLAYBOY: What will you tell your daughter when she asks about ghosts?

AYKROYD: I have to be straight with her. She hasn't brought it up, but

when she asks me, I'm going to have to say that some places have

ghosts and sometimes souls linger after life. The way to treat

them is to talk to them sharply and not let them interfere with

your existence.

PLAYBOY: How has being a father affected you?

AYKROYD: It has been a surprise just how much love you can feel and how

much love you get back.

PLAYBOY: What's it like playing to a three-year-old? Does she have a good

sense of humor?

AYKROYD: A great sense of humor. It's all sort of absurd -- mentioning

words that shouldn't be said. My only complaint is that we

waited so long to have her. We waited seven years, so we missed

seven years of enjoying her. I encourage people to have kids

early. I'm forty now, and when my daughter's twenty I'll be

approaching sixty.

PLAYBOY: Could you have appreciated being a father in the same way ten

years ago?

AYKROYD: A few months ago, Warren Beatty said something to me: "God is

very merciful because he doesn't let you know what it's like to

have children until you have them. And if you knew that feeling

before you had children you'd just yearn and want them so bad."

That veil you walk through when you have a child is something

anyone could live with at any point in life.

PLAYBOY: It's hard to believe that Warren Beatty has become a source for

parenting wisdom.

AYKROYD: I know. But of course he's just flipped out over his little

girl.

PLAYBOY: You've worked with your wife, Donna Dixon, on several films. Is

it difficult mixing work and marriage?

AYKROYD: Oh, no. It is a lot of fun. She's an extremely capable and funny

comedienne. There have been no problems. I'd do it again any

time. But now she's given up the business. She wants to be a

full-time mother and has made that commitment. It may be

temporary. She may go back to acting and she also has a

tremendous sense of interior design. She's decorated the house

in California, the two houses in Canada and the house on

Martha's Vineyard.

PLAYBOY: Why do you own so many houses?

AYKROYD: We seldom use the Martha's Vineyard house anymore, but I've had

it for a long time. We're in Los Angeles when we need to be and

we go to the family house in Canada whenever we can. There are

two houses on the property. Ours and one our friends stay in.

The property is about seventy acres with two thousand feet of

waterfront on a lake twenty-two miles long and three hundred

feet deep in some spots, they say. It's really beautiful. We

jet ski out to our island fifteen minutes down the lake and set

up camp there. I'm really fortunate I have a place to go. The

world is sort of closing in around me. They strung a set of

high-tension power lines across the farm next to ours, sort of

visual pollution if you're looking certain ways. The highway is

getting busier now and the city we live near is growing. But

then there are those magic nights after nine o'clock when you

don't hear any traffic and there's just the black sky and the

loons on the lake.

PLAYBOY: Have you ever thought of chain-sawing the towers carrying the

power lines?

AYKROYD: I wouldn't use a chain saw. I'd use muriatic acid and let the

solvent eat away at their bases over a long period of time and

bring them all down at once. But I actually don't have to worry

too much about it because a big windstorm tore down about three

of those towers. They'll rebuild them, of course, but I've

tried to rationalize the fact that the wires are there because

many UFO reports say that power lines attract UFOs.

PLAYBOY: What's your off-camera life like these days?

AYKROYD: I'm basically a recluse. I never go out anymore. I had all that

in the old days. After the Saturday Night Live shows, we went to

the Blues Bar, a place I opened down at Dominick and Hudson. It

was a private bar. We put armor on the window so we couldn't see

outside and just had wonderful nights. We would invite everybody

from the show and stay up till Sunday morning. So I've seen the

nightlife. Increasingly, it has just made me want to withdraw.

PLAYBOY: Is it simply a matter of getting older?

AYKROYD: I suppose it's that by nine-thirty at night, I'm beat. These

words are coming from the master night host of all time. I would

be standing at the door at three A.M. at the Blues Bar ready to

invite anybody in, to crank a song on the jukebox and serve

another beer.

PLAYBOY: Is there any danger that by going to bed early you lose touch

with the scene that inspired much of your work?

AYKROYD: I don't think so, not considering what I'm doing now. In fact,

I've got to conserve my energy. To do these films, I get up at

six in the morning. We work more than twelve hours a day. That's

not to say that I never burn the midnight oil. I still like to

see the dawn. About once a month I stay up all night and, the

next day, I swear I'll never drink red wine again. I have had

some spectacular campfires this summer up at the old family farm

in Canada. We go out into one of the fields with the trucks,

light a big bonfire, look at the shooting stars and let the cool

nip of a Canadian August night roll over us. I can stay up until

dawn doing that. Those late nights in the country are nectar,

absolute nectar. We try to get up there as much as we can, and

I make sure that many nights' and many days' silences are broken

by the sound of whining, whistling Harleys. I have two up there

and bikes are always welcome. I love to hear the sound of a

Harley coming down the drive.

PLAYBOY: That's an interesting mixture of sensibilities. What is it about

Harleys that so intrigues you?

AYKROYD: I think every red-blooded North American boy at some point

purchases or is given an automobile or bike that means

everything. That's why I love old cars. You climb into an old

car and it smells musty, like an old barn. It smells like your

grandfather's car. To me, that's texture. These are all the

things I worked so hard to enjoy. They're very simple. I love

cold-weather riding. Being on a backcountry highway on a summer

night with the mist rolling off the fields, smelling everything

from the thickness of manure on the land to the evening mist,

driving through a little town like Poland, New York, where

everybody has the American flag up on the white washed front

porch and kids are out on their bicycles. You roll through town

at fifteen miles an hour and take in everything. What more could

you ask for?

PLAYBOY: What more could you ask for?

AYKROYD: John Candy and I were recently marveling at how fortunate we've

been. When I met him, in 1971, he was selling Kleenex and I was

a mailman. And now we star in feature films together, work in

these great enterprises.

PLAYBOY: What movie is next?

AYKROYD: I'm not sure. They're talking about My Girl 2, which I may

become involved with. Jimmy Belushi and I are talking about

doing a Chicago police story. I'm writing a couple of things.

PLAYBOY: Are you interested in doing more dramas or do you plan to stick

to comedies?

AYKROYD: For a while all the movies -- Doctor Detroit, Neighbors,

Ghostbusters, Blues Brothers -- were comedies. I was expected to

get out there and be radical and produce laughs. I don't have an

obsession with it, but my tastes are broader than that. That's

why Driving Miss Daisy meant so much. Now I could see writing

something historical or serious.

PLAYBOY: Does the work get easier?

AYKROYD: In some ways. But a working film actor works hard. The first

thing that's hard is getting up early in the morning. The second

thing that's hard is waiting. You work when they're ready, not

when you're ready. The toughest part is when the camera's

rolling, that one or two minutes of compressed time. You are

concentrating, distilling your character. You have to do that

over and over every day. You have to shut out everything else.

It's like being a diamond cutter. When he looks up from his

work, there's the clock on the wall, other instruments, other

staff, customers, the money being counted. When he goes to cut

his diamond he has to slice that facet. If he doesn't hit it

clean, that's it. The after activities are also hard: taking

criticism, putting it out there and having people hate it.

PLAYBOY: How much do reviewers affect what you do?

AYKROYD: Sometimes the reviewers love you, sometimes they hate you, but

mostly they are mixed.

PLAYBOY: You really got knocked for your directorial debut, Nothing but

Trouble. What went wrong?

AYKROYD: It was a good little story, but the studio didn't know what to

do with it. They changed the title at the last minute --

originally it was Valkenvania. It was kind of dark and they

didn't know how to sell it. On top of that, we opened when the

Persian Gulf war was going on, Silence of the Lambs opened and

Julia Roberts' Sleeping with the Enemy had its second weekend.

We were doomed. The studio backed away from it.

PLAYBOY: Because test audiences didn't like it?

AYKROYD: Right. It wasn't what they thought it would be. But sometimes

films test bad and they go out and do business. The reviews

weren't all bad for that movie. The Toronto Star thought it was

funny.

PLAYBOY: Did you enjoy directing?

AYKROYD: A lot. But that movie set me back ten years. Nobody's going to

hand me the reins.

PLAYBOY: Even after all your other successes?

AYKROYD: Well, they may, but it will take some convincing. Nothing but

Trouble came out when I was filming My Girl, and I remember

knowing within about two days that it was all over. The way it

works now is that the people are the critics. They are the ones

who matter. The business is built on research and audience

response cards, not reviewers.

PLAYBOY: Doesn't so much reliance on feedback from audiences take a lot

of the creativity out of the business?

AYKROYD: Well, I still write movies for one person, and that's me. I'll

fight to put in some obscure technical reference that maybe

twenty people out of the millions will understand. But it's also

good to take into consideration the responses of the people,

because that's who we're making these movies for.

PLAYBOY: You once said you wished you had the money, not the fame. Is

that still true?

AYKROYD: I wish that today. The fame is worthless. It doesn't have

anything to do with the quality of my work. I could happily

dispense with it. I would much rather be paid for what I do and

not have to go home with it at night. But what am I going to do?

Moan and cry and bitch about it? I'm the only person on the

planet who's been a Ghostbuster, a Conehead and a Blues Brother.

I've had a recording career, a TV career, I won an Emmy and was

nominated for a Grammy and an Oscar. I had a number-one record,

a number-one TV show and a number-one movie. With cable and

reruns I'm going to be on the dial for the rest of my life.

PLAYBOY: Did turning forty last year mean anything for you?

AYKROYD: Age never really bothered me. Forty is just a number. Somebody

accused me of having my adolescence arrested at fifteen. It

could be true. I am forty with a cone on my head.

PLAYBOY: Do you have any sense of what people think about you?

AYKROYD: I think people perceive that whatever I do is going to be

different from what I did last. I'm perceived in the comedy

sphere mostly. I think there's curiosity about what I'm doing,

like, "What's he going to try to pull?" or, more likely, "What's

that maniac up to this time?"

PLAYBOY: Can that be a burden?

AYKROYD: Not really. I mean, I don't always have to be funny. I just like

to find out what people are thinking, I like to talk with them.

I'm just thankful that I'm not treated like one of the more

controversial figures in history. When Robert McNamara was going

to his home on Martha's Vineyard, a Vietnam vet tried to throw

him off the ferry. I'm sure Henry Kissinger takes abuse. Jane

Fonda gets it from the vets. All I have behind me is, "That

maniac made me laugh once or twice."