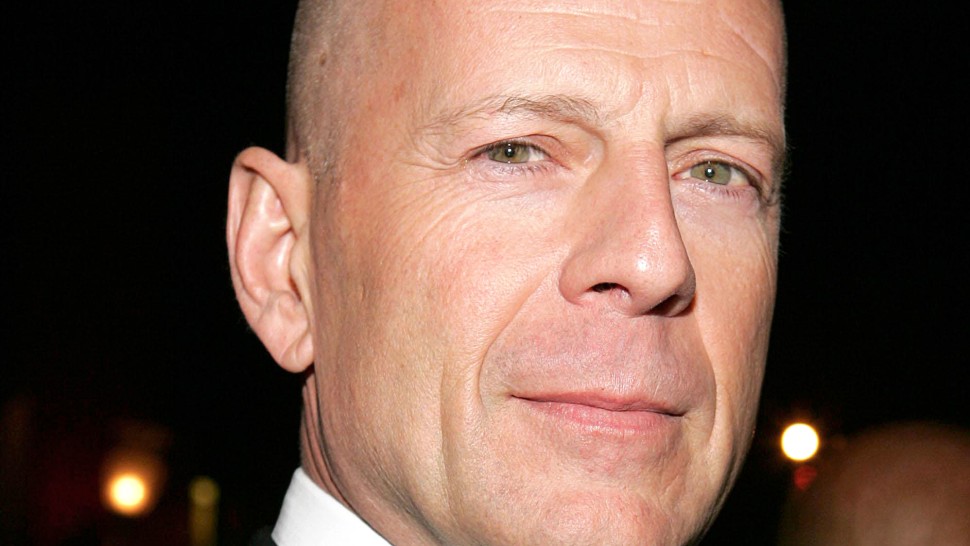

Bruce Willis

February 1996

Bruce Willis surveys the crowd at the debut of yet another Planet Hollywood, this one in San Diego. At this opening, beefy security guards whisper into walkie-talkies while celebrities such as Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Roseanne, Whoopi Goldberg, Luke Perry and Gérard Depardieu sip champagne or mineral water.

But it’s not until the music begins that the party really revs up. It’s a Planet Hollywood tradition: Willis, one of the club’s co-owners, climbs onstage and rips through a number of rock and soul songs, singing and playing harmonica. He is joined onstage by such faux rockers as Goldberg and Roseanne. Then comes the 1993 Playmate of the Year, Anna Nicole Smith, who, as The New York Times Magazine reported, “flips a breast out of the side of her red dress, waves it in Willis’ face, then unbuttons his shirt and proceeds to lick his chest.”

All in a night’s work for Bruce Willis.

As one of Hollywood’s most highly paid actors, Willis is known for movies in which property is vaporized, speed laws are broken and assorted propellants are ignited. But he is not merely a pumped-up action hero à la Schwarzenegger or Stallone. Indeed, he often chooses supporting roles in a wide range of movies for which he receives neither above-the-title credit nor big bucks. For those roles, in films such as last year’s “Nobody’s Fool,” which starred Paul Newman and Melanie Griffith, Willis has received considerable praise from critics. Terry Gilliam, who directed Willis in his most recent film, “Twelve Monkeys,” has said, “Bruce is very powerful when he’s still—not blowing up half the known universe.”

For his first thrill pic, “Die Hard,” Willis was paid a landmark $5 million (it and its tremendously popular sequels have grossed more than $700 million). “Die Hard” led to a mixed bag of films, including “The Last Boy Scout,” “Death Becomes Her,” “Striking Distance,” “Blind Date,” “In Country” and, with his wife, Demi Moore, “Mortal Thoughts.” He was also the voice-over for the annoyingly precocious baby in the “Look Who’s Talking” movies and the reporter in “Bonfire of the Vanities.” In 1994 he played Butch, the boxer who is paid to throw a fight and then refuses to go down, in Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction.”

Willis always makes an impression, in his personal life and on the screen. He was a tabloid favorite in his party-animal days and continues to be in his more respectable persona as a political mover and shaker who campaigned for George Bush in the 1992 election. There has also been an unending string of stories about his marriage to Demi Moore—a celebrated union few in Hollywood thought would last.

This high-profile, whirlwind life is a giant leap from Willis’ modest beginnings in Carneys Point, New Jersey, an industrial town on the Delaware River, where his father was a welder. His youth was typical of the time: His parents split when he was 16, he was student council president and occasional class clown and he was expelled for fighting and busted for smoking pot.

Willis stuttered when he was a child, but the speech impediment vanished when he began acting in high school. After graduating, he then enrolled at Montclair State College, where he studied theater. Next came a move to New York City, where he ardently pursued a career as an actor, paying the rent on a Hell’s Kitchen apartment with tips he made bartending. Acting jobs came slowly, first in commercials—he was the guy blowing the harmonica in a popular Levi’s ad—and finally, in 1984, as the lead in an off-Broadway production of Sam Shepard’s “Fool for Love.” From there, an agent sent him to Hollywood to audition for a TV pilot that starred Cybill Shepherd. “Moonlighting” rekindled her career and launched his.

Willis met and married Moore in 1987, and they now form Hollywood’s most powerful acting partnership (if they file jointly, the pair must pay taxes on more than $20 million a year; for her current movie, “Striptease,” Moore reportedly received $12.5 million). But they have more in common than their enormous salaries: Both actors are eager to take risks. She posed nude on the cover of “Vanity Fair” when she was seven months pregnant. In a film called “Color of Night,” he did a much-discussed underwater sex scene in which there’s a brief flash of his genitals.

Willis and Moore are completely devoted to their three daughters, Rumer, Scout and Tallulah. When he isn’t playing music or making movies, Willis divides his time between his family’s apartment on New York’s Upper West Side, a home in Malibu and an expansive ranch tucked into the mountains of Hailey, Idaho. That’s where Contributing Editor David Sheff met up with him. Here’s Sheff’s report:

“Willis and I met at his newly opened restaurant, the Mint, in a renovated former whorehouse. Downstairs is a dining area and upstairs is a club for music, comedy and dinner theater. In the entryway is a postersize photo of a precocious-looking child, captioned “Our Founder”—Willis at the age of four. The founder, now 40, with a sparse goatee and supershort haircut, escorted me upstairs to an office with leather chairs and couches, a Tiffany lamp and a long, polished mahogany bar. Above the door is a sign that reads “Be Yourself.” He said it was a gift, from his wife: ‘As far as mottoes go, it’s a pretty good one,’ he added.

“Throughout the interview, Willis was a constantly moving target, always pacing, going from the floor to the couch to a chair. He took a break in the middle of one session to have dinner with his children. When we met again an hour or so later, he picked up one of the tape recorders and, in his unmistakable whisper, said, ‘We’re back with Bruce Willis.’”

Playboy: Is it safe to hang out with you? We half expect something to blow up.

Willis: Life is taking chances, right?

Playboy: After all the movies you’ve done, does it bother you to be so closely tied to the action hero guy in the Die Hard series?

Willis: You just minimized him in a sentence. In fact, “the action hero guy” is an archetype, a classic storytelling figure. Action films serve the same function as Westerns—they present morality plays, albeit with cursing, a lot more blood and violence, and tits. The heroes are all underdogs, and in America, people love to root for the underdog. I’m drawn to them because they have obstacles to surmount. It’s more interesting than playing the George Hamilton character who shows up with the great car and the beautiful girl. When I chose those movies, I never thought about whether or not they had similarities. I thought about whether they were good stories. The only time I was conscious of doing parts that were similar was after Die Hard 2, when I was about to begin The Last Boy Scout. It was about another cop or detective, a kind of down-on-his-luck guy. I thought I should come up with a different guy—a different way of breathing, of thinking, of speaking. I think I did, though it was in a similar genre.

Playboy: The movies are similar in portraying a lot of violence. How do you respond to those who criticize all that murder and mayhem?

Willis: In my mind, a big, exciting, thrilling, scary, violent film is no different from the newest ride at Disney World. You’re sitting in a darkened room with 100 or 200 people and these little flashing points of light on the screen are able to scare you, thrill you, make you jump. That’s the trick, that’s the art form. It can make you feel good or make you cry. Some of the films I do are roller-coaster rides, some are dark character pieces and some are comedies. I don’t want to limit myself.

Playboy: Do you at least admit that the guys you play make violence seem cool?

Willis: Ever see any Humphrey Bogart movies when you were a kid? James Cagney movies? Edward G. Robinson movies? Did you ever think that that was the thing to do? See, you become a criminal because you’re a sociopath, because your parents weren’t there and you were left alone, on your own, at a time when somebody should have been saying, “This is right and this is wrong.” That’s where criminals come from. It’s not because you see Pulp Fiction.

Playboy: Yet many people think violence in movies contributes to street violence. Do you disagree?

Willis: Five hundred to 600 people have probably been “killed” in films I have done. But no one has ever said to me, “I thought so-and-so was really killed in your film.” I don’t think anyone walks out of the theater crying, “Oh my God! Forty people were killed! They’re dead!” No, Mom, they’re not dead, they’re just acting. I’ve never been shown proof that there’s any correlation between movie violence and real violence. Our audiences have the intelligence to know the difference. Bob Dole talks about Hollywood’s culpability for the violence in America. Fine. When he deals with the problems in society that cause people to kill people, we’ll talk about not doing films about people killing people. Stop crime. Let me walk out of my house and not have to think about somebody putting a gun to my head. Don’t tell me that the problem is the movies and that if we stop making all these films, anything is going to change. It isn’t. It’s a violent world. While we were shooting Twelve Monkeys, which is about a deadly virus that’s released into the atmosphere, somebody opened that jar of sarin in the Japanese subway. While I was doing publicity for Die Hard With a Vengeance, somebody blew up the building in Oklahoma City. So it’s not like this fiction is so far from reality. Fix society—don’t blame movies. Reality is what’s scary.

Playboy: David Geffen said that The Last Boy Scout was the one movie of his career that he was embarrassed to have produced because of its extreme violence. Did that one cross the line?

Willis: It’s a specific taste, but there’s an audience for it. And there was some interesting stuff in the movie. It ultimately didn’t live up to the promise of the story, but I liked the character. I know some people were offended not only by the violence but by the way the kid spoke to his father—he had a foul mouth. Sorry, Aunt Irene. It was offensive, but it made a point.

Playboy: Were you reluctant to do the Die Hard sequels, because the first one was a hard act to follow?

Willis: Yeah, especially the third time. The third in many series has had particularly bad luck. Prior to Die Hard there weren’t that many sequels, except for Sly’s work in the Rocky series. They are tough to do because they aren’t new movies. Because it’s really another chapter in a movie people have already seen, a story in which people kind of know who everybody is, you have to live up to the promise of the first film or films.

Playboy: Does the day-to-day work remain interesting?

Willis: Even in these movies, you’re trying to do new things each time. It’s not that I think I broke any new artistic ground. I didn’t come to any acting epiphanies while shooting the film—but I kept the character interesting.

Playboy: How did you get the role in the first movie?

Willis: They just asked me to do it. I was in the middle of Moonlighting. I have to thank Cybill Shepherd for enabling me to do it. She got pregnant and they shut down Moonlighting for 12 weeks. During that time, I fit in Die Hard.

Playboy: Did its success come as a surprise to you?

Willis: It definitely turned out to be bigger than what I had imagined, but I knew it was good when I saw early scenes. I think John McTiernan [the director] shone. He would do things with the camera that I wouldn’t always understand. He made it really exciting—nonstop, claustrophobic.

Playboy: Now it’s relatively modest, but your fee for Die Hard—$5 million—was unprecedented.

Willis: Yeah, it was phenomenal.

Playboy: Alan Ladd Jr., then chairman of MGM, complained that your salary was a standard that would “throw the whole movie business out of whack.”

Willis: I’m sure Alan Ladd would like to have a film that did as well as the Die Hard series has done. Leonard Goldberg, the former head of Fox who paid the money, looks like a genius. We would be having a different conversation if that film had failed. In fact, you wouldn’t be talking to me. But Goldberg took a chance. Everybody was up in arms the next day: “How can they pay this kind of dough, especially to a TV actor?”

Playboy: You are one of the highest paid actors in the world. When you reflect on your salary, do you chuckle?

Willis: Every day I wake up laughing. For whatever reason, if there is a reason, if there is destiny—I am a fortunate man. Some religions hold that I am being rewarded in this life for whatever happened to me in a past life. Whatever happened back then, I don’t know. I have no explanation for it. I’m just leading a charmed life. I have fallen into—or created—fortunate circumstances.

Playboy: And so has your wife. She broke the salary record for actresses with the $12.5 million she got for Striptease.

Willis: I can’t comment on what she actually made, but, yeah, she’s breaking a lot of barriers. It’s not a mystery. You have to be able to deliver, and she does. She hits a home run out of the park each time. I think Ghost has made something like $550 million. If she consistently makes phenomenally successful movies, as she has, she should get what guys get. Let any of these other girls open a film that goes on to earn $100 million, $150 million or more, and they’re going to get that kind of dough.

Playboy: Do you find that it changes the type of work for you when you’ve made so much money that you don’t have to work anymore?

Willis: You can become more selective about projects. For the past six, seven years I haven’t had to work on any film that has come along. Most actors take any job, because they want to work. Now I say no to things that I would have jumped at before.

Playboy: Have you said no to any movies that turned out to be hits?

Willis: How about Ghost? Knucklehead Bruce Willis. I just didn’t get it. I said, “Hey, the guy’s dead. How are you gonna have a romance?” Famous last words. But I don’t regret it, because it just doesn’t matter. It’s down the road, under the bridge.

Playboy: Ghost was your wife’s breakthrough film. In it was the provocative clay-and-sex scene with Patrick Swayze. She has also had sex scenes with Robert Redford in Indecent Proposal and Michael Douglas in Disclosure. Do you ever get jealous?

Willis: Never.

Playboy: Not even a tinge?

Willis: Not yet, no. I guess I’m not jealous in that way. I feel pretty secure with my wife and how we are with each other.

Playboy: How about the other way around? There was the story that she had one of your co-stars in Hudson Hawk fired because she was too sexy.

Willis: Bullshit. The fact is, fuck scenes are just hard work. They are the most uncomfortable acting days you will ever experience. You’re naked in front of 90 people with, most of the time, a woman you hardly know. You’re trying to develop a language of intimacy to make the scene believable. Everybody is watching. You’re bare-ass naked. You’re sweating. Some guy says, “I can see your dick. Tuck your dick in.” “I can see your breast, honey. Your nipple’s showing. Move your arm.” It’s very unsexy. By the time it gets on-screen it’s hot, but that’s a fabrication. I’ve heard stories about how some people really get into it and are lovers in real life, but that’s never happened for me.

Playboy: Did you have any hesitation about how far you went in the sex scenes in Color of Night?

Willis: I didn’t have any hesitation about doing them at the time, because the director assured me that I would be able to look at the footage and tell him what scenes I didn’t want used. I would have been able to say, “I really don’t want to see my cock dangling in the fucking pool.”

Playboy: Then what happened?

Willis: When the movie was completed, there was a big brouhaha because no one involved with getting the film out agreed with the director’s [Richard Rush’s] cut. He had his own artistic idea, which was of a much longer and more languid movie. He got territorial and thought they were taking his film away, which wasn’t the case. Everybody just wanted the movie to move faster and to be more commercial. A settlement was negotiated that allowed him to do a director’s cut for the video version. In the video, there are shots of my cock. He assured me it wouldn’t happen, but it did. I didn’t write out an agreement with him because I trusted him. And now it’s there forever on laser disc. Who cares?

Playboy: Sharon Stone says she was promised that her famous crotch shot in Basic Instinctwasn’t going to be used, either.

Willis: Well, my film didn’t do $250 million. If it had, because my dick was in it, what the hell. The point is, it’s difficult being lied to and deceived. If you tell me you’re going to do something, I take you at your word. All you have is your word and how you behave. My wife is more forgiving of bad behavior in this business than I am. I don’t forget. Demi is much more generous to people who don’t have integrity all the time. I say, “Look, either you have integrity or you don’t. And if you don’t, get the fuck out of here. I don’t want to deal with you, I don’t want to talk to you.” I don’t know if there’s any other business more ruthless than the movie industry.

Playboy: Is it frustrating that your work as an actor is so thoroughly tied to the enormous, occasionally unscrupulous, Hollywood machine?

Willis: It’s the most frustrating part of what I do. Making films and telling stories in a cinematic way is an art form, but the movie business is concerned not with art but with money. It’s all about the studios’ accumulation of large amounts of dough. If you star in their films and they’re putting all this money on the table, they are also saying, “OK, Champ, make this a big hit.” It’s easy to forget that you’re there to act. Instead, you’re pulled into the game of worrying about how much money this thing is costing, how much it’s going to make, how it’s marketed. In the past I’ve worried about all that, but now I show up as an actor and do my job and let the others worry about the rest.

Playboy: Therefore, after big-salary, mainstream films that bring in more than $100 million, is it riskier for you to take on smaller, quirkier roles?

Willis: I kind of got slung into being the star, both on TV and in movies. I never went through the phase of playing supporting roles, so I have a lot of fun doing them now. I’ve done a lot of films in the past couple years just because I wanted to do them. I have worked for little or no money. I’ve done it because I like to act and I don’t always want to be the big cheese up on the screen.

Playboy: Which of those roles are your favorites?

Willis: The ones in Nobody’s Fool, Pulp Fiction, Billy Bathgate. I just did another job for Quentin Tarantino, working for two days on his new movie, Four Rooms. Nobody’s Fool is a good example because it is such a simple movie. It’s about a man—Paul Newman’s character—who makes a small change in his life. It’s done in a subtle way, almost imperceptibly. It was very satisfying to tell a story like that.

Playboy: What was it like working with Newman?

Willis: He is unbelievable. Seventy years old and he still tries new things on every take. A guy like him wouldn’t have to; he could just show up and be the star. But he wasn’t that way for a minute. We spent a lot of time just cracking each other up. It was a guy thing, trying to break each other’s balls. It was a gas. It went by [snaps fingers] like that.

Playboy: On your most recent movie, Twelve Monkeys, you worked with Brad Pitt. How does a veteran like Paul Newman compare with a relative newcomer like Pitt?

Willis: You could draw a straight line between those guys. They both want each take to be great, each take to be different. They are there to do the work, to try to paint a picture and tell the story as interestingly as possible.

Playboy: While filming Twelve Monkeys, Pitt allegedly came to call you “O Great Bald One.”

Willis: Yeah. My head was shaved for the film, which was weird. It’s a scary, monstrous look. Fortunately, I have a nice round head. What you don’t want to do is shave and find out you have one of those misshapen pinheads.

Playboy: How did you get the role in Pulp Fiction?

Willis: Harvey Keitel’s little girl came over to the house one day to play with our girls. He came to get her. It was after he had done Bad Lieutenant and Reservoir Dogs. I was talking with him about those movies and he said, “You know, Quentin’s doing a new film. There are a lot of good parts in it. You should talk to him.” I got the script that day. Harvey happened to be having a barbecue at his house the next day and I walked down and met Quentin. We talked for a long time and I told him I wanted to be in the film. The script was so good.

Playboy: What was it that struck you?

Willis: Well, the dialogue was perfect. There’s so much real life in this wild story—that’s what I like about it. The speech I have with Maria de Medeiros at the end is an example. I’ve just gone through this hellacious morning—worst morning of my life—and we have to get out of town. But I have to take the time to ask her about her breakfast—did she get blueberry pancakes like she wanted? I know every guy in America understood that moment. I’m dying, my nose is broken, I’m bloody and gashed up. “Oh, you didn’t get the blueberry pancakes? I’m so sorry. What happened?” It was a great, great moment. And it was part of what made the film great.

Playboy: You’ve had some good luck with reviews, including those for Pulp Fiction, and some bad luck. How much power do critics have?

Willis: If they put their mind to it, they can crush a movie or an actor. The critical media in general can conspire to make people feel fucking stupid if they see a movie. It happened with Hudson Hawk. It had nothing to do with the film.

Playboy: Could that be sour grapes because the film was trashed?

Willis: No, because they were reviewing Hudson Hawk before anyone saw a frame of it. It was just my time to catch a beating in the press.

Playboy: It sounds as if you imagine a conspiracy of critics sitting around in a room saying, “Let’s get Willis.”

Willis: That’s almost what happens. They get together, go on these press junkets, hang out, influence one another. It doesn’t happen by accident. A couple years ago it happened to Arnold Schwarzenegger. Last Action Hero was no better or worse than any other Schwarzenegger film. But it was time for Arnold to catch it. We heard that the movie was a bomb before it was released. Look at what happened with Kevin Costner’s Waterworld. Before anyone saw a frame, they were saying, “Bomb.” The way it works is that the media imply that everybody involved in the movie is stupid and you’re stupid if you see it. That sentiment can gain momentum. Soon you hear “Waterworld” and you go, “Ugh.” After the criticism I received for Hudson Hawk, I stood back and looked at how much power I was giving to these people. I thought, If they say I’m good, am I good? If they say I suck, do I suck? I realized that wasn’t the scale by which to measure oneself.

Playboy: Have the critics always been wrong when they have trashed your movies?

Willis: The only movie I would not do again, given the opportunity, is Bonfire of the Vanities.

Playboy: What went wrong with that movie?

Willis: It was stillborn, dead before it ever got out of the box. It was another film that was reviewed before it hit the screen. The critical media didn’t want to see a movie that cast the literary world in a shady light. In the reviews, they were recasting the film. They were saying, “If we were doing this film, we would cast William Hurt instead of Tom Hanks,” or whatever. Well, if you were doing the film, then that might mean you had some fucking talent and knew how to tell a story instead of writing about what other people are trying to do. But they were right. I was miscast. I know that Tom Hanks thinks he was, too. The movie was based on a great book. But one problem with the story, when it came to the film, was that there was no one in it you could root for. In most successful movies, there’s someone to cheer on.

Playboy: You were also taken to task in The Devil’s Candy, a brutal book about the making of the Bonfire movie written by Julie Salamon. Among much more, she said, “[Willis] was trapped by the limitations of his range.”

Willis: Brian De Palma chose to have this girl come on the set and write a book about the making of the film. But he neglected to tell the actors about it until she had already been skulking around for about four weeks. By the time we learned what she was doing, the damage was done. Basically, she decided to take a big shit on a bunch of people she would never get to be in her own life. I can say this about her: She had the worst fucking breath of any organism I have ever encountered on the planet. You had to turn away when she talked to you. Julie Salamon and her ilk are parasites. It’s just one of the more unpleasant things about being a public figure. They can say anything about you and they hound you. It’s like anything else bad in the world. Air pollution. Car accidents. I know we could probably go out to some newsstand right now and find something shitty that somebody has said about me. It sells magazines. So to all those people who have written shitty things about me for the past 11 years: Fuck you. I’m still here.

Playboy: Because you are under scrutiny by the press, are you more sympathetic when you read about scandals involving your peers?

Willis: Yeah, and I know how much is completely made up. People think that if it’s written down, it must be true. Whatever they want to say is fine, man. Some of the harshest things ever said about anybody have been said about me. I just walk through it. Somebody’s making money. It’s a really shitty side of show business. It trades in human foibles, human tragedy, human misbehavior and humiliation. And most of it isn’t true. All they give a fuck about is selling this shit in the stores.

Playboy: So is it safe to assume that one recent press report—about Anna Nicole Smith licking your chest at an opening for one of your Planet Hollywood restaurants—is untrue?

Willis: [Laughs] All right. She did not lick my chest. As they say in sex movies, she simulated the act of licking me. She had a bit too much to drink, that’s all. She was just a little frisky. It happens to everybody.

Playboy: And what about her exposing her breast onstage?

Willis: I didn’t actually see the alleged breast incident, because I had retreated to the guitar area of the stage. But I heard stories about it: that she flung it out, in one version, and that she lifted it out and set it on the tray of a waiter who happened to be passing by. There was every kind of fucking story. What I think actually happened is that one of them just shook loose. Some women wear scanty outfits, and she’s a big girl.

Playboy: So when was the last time you hit someone?

Willis: I haven’t hit anybody, I don’t know, probably since the early Eighties. I came close to smacking somebody at the Die Hard With a Vengeance premiere. I’m having a great time. There’s a guy—I’m not going to tell you who—and I’m sure his boss had told him, “Go be an asshole and try to instigate something.” But for no reason—as far as I knew at the time—this guy is saying shit about my old lady. He’s going, “Are you gonna dump Demi when she gets dumpy?” Shit like that. I’m like, “What is this, fucking Satan here?” I say, “Hey, what’s the matter with you?” A little later he’s saying something else shitty to me. I say, “Hey, motherfucker, what’s wrong with you? Stop! Get out of here.” I tell somebody about him and they go to throw him out, but he sneaks around again. I’m standing there talking to somebody and he says one more really shitty thing about my wife. I was this close. “Hey, let me explain something to you. You may think I’m a fucking celebrity and above punching your lights out, but you’re a fucking cunt hair away from going down and having to spit your fucking teeth out.” It stopped after that. That was the closest I’ve come in a long time.

Playboy: Are you extra careful because you could be sued?

Willis: Yeah. Once you become a public figure, all someone has to do is take a swing at you, and if you hit them, you can be sued. They have a good shot at getting some money, at least a settlement. I’m not interested in getting fucked like that. People ask why I have bodyguards. For two reasons. One is for my kids, when I travel with them. The other isn’t to protect me from people but to protect other people from me. I don’t want to punch somebody’s lights out and then get sued.

Playboy: Is it your nature just to start swinging?

Willis: Let’s just say there are some things about me that I’ll never completely eliminate. One is that there’s only so far I’ll go, and then I’m going to hit you, no matter what. I don’t give a fuck if I have to pay a million dollars. I can be gotten to. I wanted to punch someone the other day after I saw this talk show. If these shows were really about helping people—if they were really about helping child molesters or their victims—you might see another side. But there is no other side. I saw a Maury Povich show on which he had nine- and ten-year-old children who had watched their moms and dads shoot each other. For the opening of the show, they played tapes of the 911 calls. The kids are screaming [mimics a child screaming] and then you hear pow! pow!, then more screams. Then Povich interviews the kids and gets them crying again. They play the tape again, this time while the kids are sitting there. I wanted to punch Maury Povich in the fucking face. He’s making money off of these children. Somewhere in some sleazy, slime-encrusted back room, money is changing hands—from the people who advertise on Maury Povich’s fucking show to these little kids, who not only had to go through it but have to relive it. The producers justify it by saying, “Here, son, we’re going to pay you. Here’s some money.” It’s the downfall of fucking civilization. You tell me we’re a civilized planet? Watch any of these shows any day.

Playboy: Yet people choose to spill their guts on talk shows.

Willis: People want to be famous. They want to get on TV any fucking way. “I’ll tell you how I fucked my little doggy if you put me on TV.” They will talk about the shittiest things. It’s not their fault, because they don’t know that you should just keep your mouth shut and not embarrass yourself. The ones to blame are the ones cashing in. It’s not just Maury Povich and his ilk. It’s also the people behind the scenes who say, “Yeah, run that story, go with the 911 tape. Beautiful, Maury. Gorgeous. Think of the ratings!” They are all making money off someone else’s misfortune. The fucking whores. Imagine where it’s going: televised executions, the 24-hour Violence Channel, on which you can see somebody get whacked over the fucking head with a shovel or something.

Playboy: Many of these tabloid shows have another favorite topic—you and your marriage. How much of a burden is this treatment?

Willis: It’s irrelevant. We laugh it off. I always know when there’s a lull in the tabloid market—when nobody’s fucking up—because they always come up with the “Bruce Willis and Demi Moore Are Breaking Up!” story. It has happened once or twice a year since we got married. It’s just gotten to be funny. Those shows and magazines are outside the realm. I don’t need to hear that I was on a horse and saved a little girl from drowning in a fucking stream or some cockamamie thing. People think the National Enquirer is a newspaper.

Playboy: How did you and Demi meet?

Willis: We were both at a screening of an Emilio Estevez–Richard Dreyfuss movie called Stakeout.

Playboy: Though she was going out with Estevez at the time, was it an instant attraction?

Willis: We got married four months later, so I guess I wouldn’t call it instant. But it was rapid. I was enamored pretty quickly.

Playboy: We heard that Little Richard presided at your wedding.

Willis: That was later. First we married in Las Vegas and then a friend was kind enough to throw us a huge wedding party on a soundstage in Hollywood. We invited all our friends. When we were married the first time it was me, Demi, the reverend, a friend of mine and a friend of hers in a hotel room at the Golden Nugget.

Playboy: Was the wedding in Vegas spontaneous?

Willis: We had been talking about it for a while, then happened to go there to see a fight. I said, “You know, we could walk down to the little wedding chapel and get married,” and she laughed. We joked about it, and later that night she said, “Let’s go.” I said, “Well, let me finish this one hand.…” [laughs] I called these guys I knew and they pushed some buttons and—boom—it’ll be nine years.

Playboy: That’s a reasonable accomplishment in Hollywood. You’ve survived the seven-year itch.

Willis: We both get asked, “How do you do it? How do you work this magical fairy tale of a life? How do you juggle it all?” The answer is: I don’t know. The fact is, this is the longest either of us has stayed with anybody, so we’re in uncharted waters. We deal with it one day at a time.

Playboy: What was it like working together in Mortal Thoughts?

Willis: I worked only about ten days on that film, but it was great. There was no husband-wife “I’m the boss, you’re not the boss” thing. That was my favorite movie until Pulp Fiction.

Playboy: Would you say that you are both fairly headstrong?

Willis: Yeah. But we’re both smart enough to know the truth when we hear it. I don’t really give a shit about being in charge. I don’t give a shit about being the boss. I just want to make it a good story, so we work out whatever comes up.

Playboy: How about at home?

Willis: We’ve gotten pretty good at it. We each have things that we acquiesce about. There are certain areas she handles better than I do. There are certain areas I handle better.

Playboy: What do Bruce Willis and Demi Moore fight about?

Willis: Same stuff as anybody. Just the little things that come up. We’ve kind of found our spots and our way of sharing the responsibility.

Playboy: When you’re on location, does your family stay home?

Willis: We all travel like a big circus. Like gypsies. And when we’re not working, we split our time between our ranch and New York City. The children are in school near the ranch. I spend every second I can with them. After I finished Pulp Fiction and before I started Die Hard With a Vengeance, I had eight months off and was with them every day.

Playboy: When you had your first child, did you have to learn how to be a father?

Willis: I was prepared for it. I don’t know how I learned, but it was never hard and I never had to make a major adjustment. I was ready to be a nurturing, caring, hold-my-baby father. I pulled all three of them out. Caught them.

Playboy: We all saw your wife when she was pregnant on the famous Vanity Fair cover. What did you think of it?

Willis: It was incredible. She really goes out of her way to push the envelope, and I admire that. Most people loved it—women said they felt it was a celebration of womanhood and motherhood. And there were some negative reactions, which came once again from the parochial attitudes of America. Something as pristine as motherhood, as bringing a child into the world, was somehow turned around to be something bad, especially down South. They were pulling the magazine off the stands. Yet I thought it was the strongest affirmation of motherhood and womanhood that I have seen out of the past 100 years.

Playboy: The reaction against a woman who shows her pregnant body is similar to the one against women who breast-feed their babies in public.

Willis: We got that, too. My wife just said, “Hey, you know what? Go fuck yourself. This is my child and I’m going to feed her when and where she is hungry.”

Playboy: Do you think your parents were good teachers?

Willis: No, though I don’t blame them or anyone from that generation. They just had much less information about what children need.

Playboy: What was your hometown like?

Willis: A small place, 6,000 or 7,000 people, on the Delaware River in south Jersey. My father was a welder, master mechanic and pipe fitter. I come from a long line of mechanics and handymen.

Playboy: And when did you lose your virginity?

Willis: Early.

Playboy: Do you remember her name?

Willis: You would think so, but I don’t.

Playboy: How traumatic was it when your parents split up?

Willis: As traumatic as it is for anybody. I was the oldest, so I had a little more awareness of the problem and the tension in our house. Our family kind of exploded and everybody went off on their own. Gradually, the kids came back together and had an even tighter bond because of the experience. At the time, I stayed with my dad, and my two younger brothers went to live with my mom.

Playboy: What was the impact?

Willis: I’m sure I was affected by it. I know I’m never going to stay in a marriage if I’m really unhappy. I don’t think anybody should. Life is too short to spend what little precious time you have alive being unhappy.

Playboy: Were you a good student?

Willis: I did all right, especially in the humanities. The best thing I got out of school was an enjoyment of reading. But I went into high school in 1968. We did everything everybody did at that time. Smoked dope, learned to drink early, hung out.

Playboy: You were kicked out of school, weren’t you?

Willis: When I was a senior I was expelled because I was involved in what was called a race riot. In retrospect, I don’t think it had as much to do with race as it did with 17- and 18-year-old guys looking to fight. They expelled 25 white kids and 25 black kids. I ended up missing the last three months of my senior year. I was pretty shook up by that. [laughs] I’m being sarcastic. I had a ball.

Playboy: You stuttered but found that it stopped when you were onstage. Did you figure out why?

Willis: When I acted I was being a different person. The emotional trigger that caused me to stutter—I don’t know what the fuck it was—stopped when I would act. Finally, I told myself I wasn’t going to be affected by it, and I grew out of it.

Playboy: Weren’t you once busted for dope?

Willis: For two joints, one behind each ear. I was taken off to the calaboose. I was 19. At the time it was a misdemeanor. I inhaled.

Playboy: When did you first act?

Willis: In high school. I was always into it, though. I trace it back to when I was in the Cub Scouts. We did a skit in the Scout jamboree that got a big laugh. There were 500 people on this hillside and we got this huge, thunderous laugh. I went, “Oh, wow, that is an interesting feeling.” As soon as I got to college and auditioned for my first play, I said, “This is it.”

Playboy: Was your plan to be in the theater in New York?

Willis: Yeah. The college I went to was 20 minutes outside New York, in north Jersey. By my second year I was sneaking out of class to audition for plays. In 1976 I left school and never looked back. With each job I got a little better.

Playboy: Did you make a living working as an actor?

Willis: I made a living by tending bar, mostly.

Playboy: You knew John Goodman in those days, right?

Willis: Yeah. John was one of the gang. He really kicked it off when he got this John Deere commercial. Everybody thought, Wow, man, Goodman’s got a John Deere commercial! I used to do a lot of extra work in commercials, too. Then I got a Levi’s commercial and made some good dough for the first time, when a hundred bucks seemed like a million. Soon after that, I got a part in the play Fool for Love, and from that I got an agent. The agent sent me to Hollywood to try out for a little job called Moonlighting.

Playboy: Did you know the show would be your big break?

Willis: I had no idea. It was just another job for me. I thought, TV pilots? Dime a dozen. I thought I would do this pilot and go back to New York. But it caught on and became—boom!—this thing. It was just magic. I would hold up the original pilot against anything that’s ever been on TV. It was like an experimental theater group. We were doing something that was on the edge. There were hardly any rules. Cybill was fabulous. Particularly in the first few years, we were both really jamming.

Playboy: Besides great lines, overlapping dialogue, occasional jokes in the direction of the viewer and intriguing plots, the show sizzled because of the relationship between your character and Cybill Shepherd’s. The fights you and she had—on-screen and offscreen—became legend.

Willis: It’s like any rumor that gets blown out of proportion. We would disagree about how scenes should be played, but that’s part of the process. Ultimately the only thing that matters is what serves the story. They chose to say we were fighting about it. It sold a lot more National Enquirers to say that we were fighting than to say, “Nothing happened this week on Moonlighting.”

Playboy: And then there was the sexual chemistry, which was, in the words of one writer, “hot enough to bend Plexiglas.” Was it just good acting?

Willis: There were hot days, days when things might have sparked or something. But there was nothing to report. It wasn’t like we were in love with each other or there was any kind of romance going on. If anything, at the end of the day we were sick of each other; we were together all day, every day, in almost every scene.

Playboy: Around that time you became famous for your partying.

Willis: That was the middle of my so-called wild years. It was partly a lack of having anything to be responsible to. Now I have children and a wife and an extended family. I have a job, too. When I say “Yes, I will do this job,” 150 other people get a job because of it. Before, I was a singular organism moving through the universe. It’s not like I was ever out in a car drunk, running down little kids. But I was playing my music loud and partying with my friends.

Playboy: And you were arrested for disturbing the peace.

Willis: Yeah, and I guess disturbing the peace is a fairly serious crime, right up there with drive-by shooting, kidnapping and setting the Los Angeles hills on fire.

Playboy: What actually happened?

Willis: The disturbing the peace thing came because I had brought a New York party sense to Los Angeles. In New York, you live right next door to and above your neighbors. You do your thing and they do their thing. You party, you do whatever you want. When I moved to L.A., I got a house in the Hollywood Hills, in a residential neighborhood, and I was jamming with my friends all night. I was single, and I was in and out, people around all the time, all hours of the night. I was stupid. I was rude to my neighbors, and I just didn’t think about it until it was too late.

Playboy: Are all of your vices behind you now?

Willis: Yeah. I still do dangerous things, but I have cut way down. I have a much stronger awareness of my own mortality. I’m much more careful than I used to be. I wear a helmet when I ride my motorcycle. I don’t need my kids saying, “Oh, Daddy fell off his motorcycle and cracked his head open. Now we have no more Daddy.” I consider the consequences of things, which I never did before. I take my children into consideration before I make any decision. I’m more interested in my children than anything else. You have the opportunity to do so much for your kids when they are very young. That’s a gift I’m fortunate enough to be able to give my kids—me. My time. So many fathers work 12, 14 hours a day, 50 weeks a year, just to keep the money and the machine moving. I’m fortunate, and I think my kids will benefit from it. The fact that parents don’t have time for their kids is one of the biggest problems. And how bad the school system is. For kids who don’t have strong families, the only chance they have is if the schools do their job. It’s a problem that could be solved in—I’m going to guess—five years. If the government just threw money at it, in five years I guarantee you it would be a lot better than it is now.

Playboy: Yet many of your fellow Republicans say money isn’t the problem.

Willis: It is the only problem. You can’t raise a family on a schoolteacher’s salary. If salaries were doubled, you would have so many good people going back to teaching. Great teachers—smart people who want to teach but simply can’t because they can’t afford to make $17,500 a year. Whatever the fuck the money is being used for, give it to teachers. Don’t build a shuttle, OK? Take that off the list this year and give it to the schools. Take the money we spend right now to defend Japan. Send them a bill for it, at cost—wholesale. Spend that money on schools. Raise teachers’ salaries. I’m sure the politicians can come up with a thousand reasons why it can’t be done, but I bet if they just tried, it would make a huge difference. [shaking his head] I have great problems with government.

Playboy: Yet you were a vocal Bush supporter in the last campaign. Republicans are notoriously tougher on education spending than Democrats.

Willis: I’m not going to defend that. There are a lot of things about both parties that I don’t agree with. I’m a Republican because I believe some of what they choose to believe: that smaller government and less government is better, and, ultimately, lower taxes. But first you have to spend money on education, on helping people who can’t eat. It’s common sense. It goes without saying: Take care of the elderly people who can’t do it themselves; take care of the kids who can’t eat.

Playboy: You’re sounding more like a Democrat all the time.

Willis: The Republicans, though, want to cut waste and taxes. Now there’s no accountability from the time the money leaves your pocket, daddy-o. I envision a big pile of $100 bills up there in Washington, and they’re all taking a piss on it. “Oh, there’s one! You didn’t get that one!” Can’t we have accountability for 35 percent or 28 percent or 50 percent of every dollar we earn?

Playboy: How serious is your interest in politics?

Willis: My checkered past will always keep me out of politics. Unless they start grading on a curve, I’m not going to get in. But I do know what we need: to clean house. Get them all the fuck out. Start over and put my dad and your cousin and your nephew and my aunt in. Say, “Figure it out and do the right thing. Start by watching the dough.” There are a lot of good ideas down there that just aren’t being considered because people are making too much fucking money off of not doing the right thing. Like: “Oh, there’s too much crack! Kids are dying? The cocaine thing is an epidemic?” How about we declare war on Colombia? It’s over or we’re coming in and we’re going to make you the 51st state. But somebody is making money off this. Billions, hundreds of billions, gigabillions. Whatever the fuck—the biggest amount. Houses of cash. Is there any doubt that some of it isn’t bleeding up to Washington somewhere? It couldn’t exist without somebody looking the other way.

Whenever it comes time for the government to make a correction for past abuses, Congress shirks its responsibility. It just voted down a law about taking money from lobbyists. Where are term limits, the line-item veto and lower taxes? No one will follow through on any of that—neither party. I am a big contributor to the U.S. Treasury. Half of every dollar goes to the government. It’s a partner with me right down the line. The inheritance tax. Your dad or anybody’s dad works his whole life to pay off a 30-year mortgage. At the end of it, when he dies, if his kids don’t have the tax money, if they can’t come up with 50 percent of the value of it, it gets taken away. That is not a government that’s there to serve. That’s just theft. It’s stealing. And the government gets away with it. I would feel better about it if the money were going anywhere besides into this big pile in the backyard that they’re all pissing on. It’s why I got involved in the last election.

Playboy: Will you be involved in 1996?

Willis: We’ll see what happens this spring. We’ll see how things shake out.

Playboy: As the father of three girls, what can you teach your daughters that their mom can’t?

Willis: The only gift that I really see myself giving them is the truth about guys.

Playboy: Which is?

Willis: You know the truth about guys. What were you thinking about when you were 17 years old? The same thing I was thinking about. The same thing every 17-year-old guy thinks about. That’s the information my girls have to get. I’ll say, “Look, you’ve got to understand: This is your body. It belongs to you. No one can touch it, no one can take it away from you. No one can get in there without your saying so. You have to have enough knowledge and enough strength to know that it’s your choice.”

Playboy: On the other hand, what would you tell boys?

Willis: “Go get ’em, guys!” [laughs] It’s a whole different speech. It’s just acknowledging reality. I read Robert Wright’s The Moral Animal, in which he sums it up. He presents the thesis that everything we do—as men and women—is in response to a genetic impulse to do one thing and one thing only: Get our genes into the next generation. It explains everything. I read it and went, “Oh fuck, of course! That’s it.” I could go back and explain every move I ever made with that in mind. Perpetuate the gene pool, man. It explains everything we see going on around us—politics, money, war. We try hard, but we’re animals. We’re just donkeys walking up to the trough for food and wanting to fuck everything we see because of this unconscious agenda. If you’re heterosexual and you are honest, you must admit that the first thing that comes to mind when you look at a woman is, Hey, I’d like to fuck her. We have to admit it. It’s programmed in our genetic map. You’re not thinking, Oh, there’s a good childbearer. I could have a good brood of apes with her. It’s unconscious. All you’re thinking is, Mmmm, yes. I’ll take you and you.…

Playboy: This is why, Wright points out, fidelity isn’t always easy. Is that true even when you’re married to Demi Moore?

Willis: [Laughs] Of course. It’s why keeping any relationship going is such a struggle. We balance our responsibilities as parents and adults with our needs as individuals. You compromise, you sacrifice, you decide what you will and won’t do. But the reason it’s such a struggle is that we are human beings who were, not long ago, stomping around in the world, trying to fuck all the time to ensure the survival of our line. Wright says that out of all known human societies, the monogamous ones were a small minority. Everybody else was going fucking nuts.

Playboy: You sound like a reluctantly monogamous man.

Willis: Let’s be honest about what it takes. What is marriage? No woman is going to satisfy a man’s natural impulse to procreate, procreate, procreate. The impulse doesn’t go away because you have three or ten or a hundred kids. On an emotional level, to think that you are going to find one person who understands what you need right now and is able to give it to you, to anticipate what you will need ten years from now, 20 years from now, 30 years from now—for the rest of your natural fucking life—is a myth. Yet that’s what marriage is based on. If you’re lucky, you might get 70 percent of your needs met. Maybe 80 percent. Probably 50 percent sometimes, and sometimes you don’t get any of your needs met. It’s crazy, against our nature, but we choose to continue because it has other values. I’m still doing it. And I choose to believe it is worth it.

Playboy: Is it worth it?

Willis: Yes, even with the knowledge that marriage is a myth. In fact, our marriage works because we both understand that it is a myth to think, I’ve found the perfect person and my life is fine now. It’s a garden. You have to tend it every day. You water it, you keep the weeds out. In my early life, whenever I had a problem, a big problem, it was, “OK we’re breaking up. Done. Over.” Demi and I have had problems that ten or 15 years ago would have made me walk. Now I know that it’s just a valley and I have to hang in long enough to get back up on the hill. It’s a hard gig. You’ve got to keep moving forward. We both know it’s not guaranteed. We’re in it together and trying hard.

Playboy: Is it tougher or easier because you’re both in the same high-profile business?

Willis: I don’t know if any marriage could be harder than when both people do the exact same fucking thing, when they are, in the eyes of the world, big shots—celebrities, superstars, whatever you want to say. We both do the same thing, both travel all the time. We both average 300 hours a year on planes. On the other hand, when I come home after a day at work, how many people are really going to understand what I’ve been through? She’s one of a few.

Playboy: But in most jobs, you would come home at night and be with your wife. In yours, you can be isolated on a set for months with another beautiful woman. Many marriages involving movie stars fail because of those kinds of circumstances.

Willis: The time apart is, to a certain degree, controllable. But the opportunity to do anything bad, whether it’s cheat on your wife, kill someone, take a drug, commit a crime—whatever—is always there. I truly believe that in every human being there’s an ongoing struggle between good and evil. As that guy who is still getting the information from a 150-million-year-old genetic map inside of me, it’s difficult. But I choose to stay monogamous, not to fuck around. I believe it’s the right thing to do. Is the opportunity there all the time? Yeah, all the time. Every day. It’s an adult choice, certainly, compared to the choices I made when I was 20 years old, when I was led around by my dick. Whoever I wanted to fuck, I’d fuck, whether or not I had a girlfriend. Done. Now I’m old enough to make an adult choice and not agonize over it. I know that I am choosing to be with my wife and to stay with my wife.

Playboy: You are both extremely successful. What would happen if one of you had five bad years while the other were still soaring?

Willis: Here’s a short answer to that question: I don’t know how to play the “What if?” game. You may as well ask, “What would happen if you died tomorrow?” I don’t know if that’s going to happen, either. I refuse to speculate. Sure, it’d be fucked up if all of a sudden I’m flipping burgers or I’m on Hollywood Squares. You know what I mean? “I’ll take Bruce Willis to block.” I’d get some Moonlighting question. I know this: I don’t have anything to say about when I die. I don’t know when it’s going to happen or how it’s going to happen. I don’t know if I’m going to live to be old or die tomorrow. What I do know is that I’m going to try to eat it all up today. Squeeze as much fun out of each day as I can. I know that’s an important thing because—boom!—I could be gone.

Playboy: Was any of this new to you since you hit 40?

Willis: No. I was surprised how seamless it was to turn 40. I have a lot of things going for me. I’m in the best shape of my life. I’ve got a couple dollars in my pocket. I have a great family and great friends. Forty feels great. In my heart I’m like 22 anyway. I believe that around me are things I pulled into my orbit, things I made happen. I’ll take responsibility for them—it’s not like God put them there. I feel good about what’s around me because I worked hard for it.

Playboy: Moonlighting’s producer, Glenn Caron, once said: “Deep at his core I think Bruce is very shy. He became very cocky to compensate.” Does that make any sense?

Willis: A lot of people don’t know that Glenn was a psychologist before he became a writer and executive producer. Who knows? Maybe. For me cockiness is just a verbal tool. I think people generally confuse confidence with being cocky. Cocky is when you act confident but you can’t really back it up. If you are confident, you can do what you say you can do. I’ve always been fairly secure in what I think about things and how I move in the world. I guess that’s a form of confidence. People who are not confident are intimidated by that kind of confidence. It has nothing to do with being successful or famous; I experienced that 15 years before I was famous. But, hell, who cares? I’ve been called cocky by some of the best writers our country has to offer. And they all seem to remark on “that smirk.” Hey, this is my face. This is just how I look. This is how I smile—crooked. I smile to the side. When Moonlighting first came on, everyone said, “Oh, the smirk. We love him. Look how charming he is with that fucking smirk.” Then, all of a sudden, it became this negative thing. “Oh, he’s smirking. I’d like to wipe that smirk off his face.” I’m sure they’d like to barbecue me, but it’s just the way I happen to smile. So anyway, being 40 is fine. The only thing I have really figured out in 40 years is how I want to live my life now. Try to do good things. Try to help people. Help my family, my friends. Try to live my life as a good man.

Playboy: Anything else?

Willis: Yeah, you can print this caveat at the end of the interview if you want. If I have offended anyone during the previous discourse in which I reflected on how I feel about any number of things in the world: (A) I had no idea what I was saying or that they would print it. (B) It is my personal opinion and does not reflect the opinion of any group or organization. Take it or leave it at that. (C) Go fuck yourself.